Internal Medicine

Treatment of ionised hypercalcaemia in cats

When to measure blood calcium in cats and why do we worry?

Clinical signs of hypercalcaemia include PUPD, weakness, depression, anorexia, vomiting, constipation, muscle twitching and cardiac arrhythmias. Often hypercalcaemia is detected on routine bloods as an incidental finding. The detection of ionised hypercalcaemia should always be investigated further and appropriate management instigated.

Chronic, untreated hypercalcaemia can lead to many deleterious effects, most notably in the kidney. Renal complications include ischaemic renal damage, soft tissue calcification and irreversible renal failure. Calciuria predisposes to renoliths and uroliths.

How to measure blood calcium in cats?

Routine in house biochemistry analysers provide a total blood calcium level. This reflects protein bound, complexed and ionised calcium and is therefore affected by many variables. When we need to know the true calcium status of a cat, we must measure ionised calcium. This is the physiologically active form which is normally kept within a tight reference range.

Total blood calcium is not an appropriate substitute for measuring ionised calcium as there is substantial discordance between these values. A study showed that 64% of cats confirmed as hypercalcaemic by ionised calcium measurement, had a normal total blood calcium1.

What causes hypercalcaemia in cats?

Idiopathic hypercalcaemia is the most common cause and is a diagnosis of exclusion. Other common causes include chronic kidney disease (although these cases usually have a high total calcium with a low ionised calcium) and hypercalcaemia of malignancy.

Less common causes include primary hyperparathyroidism, granulomatous disease (e.g. toxoplasmosis, FIP and mycobacterial infections), hypervitaminosis D (due to ingestion of topical psoriasis creams, calciferol containing rodenticides, some plants or excess vitamin D in the diet) and diseases causing destruction of bone (e.g. primary bone tumours, metastases to bone and osteomyelitis). A very rare cause is hypoadrenocorticism.

Dietary management of idiopathic hypercalcaemia

A change in diet is usually the first treatment trialled. Several diets have been suggested, reflecting the fact that no single diet will be consistently effective for all cases. Canned diets are recommended over dry foods due to the higher moisture content. Options include:

- Diets which have increased dietary fibre such as Hills W/D, Purina OM or Royal Canin Gastrointestinal Fibre Response. The theory is that the supplemental fibre will bind intestinal calcium, thereby preventing its absorption.

- Renal diets can be beneficial, but the exact mechanism is unknown. These diets have lower calcium and phosphorous concentrations, and are also less acidifying than maintenance diets.

- Urolithiasis diets designed to prevent calcium oxalate uroliths such as Royal Canin SO, Purina Urinary St/Ox or Hills C/D can also be trialled.

Medical management of idiopathic hypercalcaemia

If a change in diet is not successful in lowering ionised calcium in 6-8 weeks, medical management is advised.

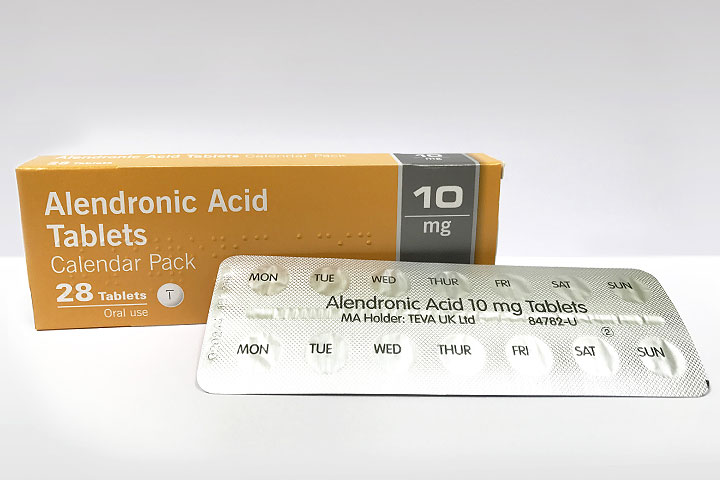

Bisphosphonates

- Bisphosphonates are now considered to the first line treatment of idiopathic hypercalcaemia in cats. These drugs decrease osteoclastic bone resorption. They are generally considered safer than glucocorticoids, due to less common side effects.

- Alendronate (alendronic acid) has very poor oral bioavailability. Only 3% of the drug is absorbed by cats when given with water alone2.This absorption is dramatically worsened by the presence of food. It is recommended that cats are fasted overnight for 12 hours before being medicated, and fed two hours later.

- The main risk associated with oral alendronate treatment is erosive oesophagitis and secondary oesophageal stricture formation. At least 6ml of water should be syringed into the cat’s mouth after tableting to ensure quick passage of the tablet into the stomach. Butter on the cat’s lips can increase salivation and swallowing.

- The starting dose is generally 10mg/cat (not per kg) per week. Blood calcium should be rechecked after 4 weeks. It is recommended that whole tablets are used (i.e. not split) to avoid toxic injury to the oesophagus, therefore available tablet size may dictate what dose increase can be made if the cat remains hypercalcaemic. If only 10mg tablets are available, you could consider using alternate weekly doses of 10mg and 20mg to create an average dose of 15mg per week. If the ionised calcium is normal, bloods should be re-evaluated every 1, 3 and 4 to 6 months.

- Oral alendronate is generally considered safe at doses of between 5 to 20mg per week, with rare risks of mild clinically insignificant ionised hypocalcaemia3. The safety of alendronate therapy in cats with chronic kidney disease has not been specifically studied, however 2 cats with CKD were followed in that study and no deterioration in renal function was seen over a 6 month period.

- A rare side effects associated with chronic alendronate treatment is osteonecrosis of the jaw. This has been reported in humans and dogs, but not in cats. Chronic bisphosphonate therapy can also lead to brittle bones in humans and an increased risk of bone fractures.

Glucocorticoids

- Steroids can be effective in restoring normocalcaemia. Due to their adverse effects (PUPD, polyphagia and induction of diabetes mellitus) they are usually considered a second line treatment when bisphosphonates have failed (i.e. a dose of 30-40mg alendronate weekly has been unsuccessful in lowering blood calcium).

- Steroids will decrease intestinal calcium absorption, decrease renal tubular calcium reabsorption and decrease skeletal mobilisation of calcium.

- Prednisolone at a starting dose of 1mg/kg/day has been recommended, with ionised calcium repeated one month later. Dose escalation is often required to achieve sufficient lowering of ionised calcium, and the beneficial effect may be transient.

- It is important that steroids are not prescribed before lymphoma is excluded as a cause of hypercalcaemia, due to the cytolytic effects of steroids on lymphocytes.

1. Schenk, P.A. & Chew, D. J. (2010). Prediction of serum ionised calcium concentration by serum total calcium measurement in cats. Canadian Journal of Vet Research 3, 209-213.

2. Mohn, K.L., Jacks, T.M., Schleim, K.D., et al. (2009) Alendronate binds to tooth rooth surfaces and inhibits progression of feline tooth resorption: a pilot proof-of-concept study. Journal of Veterinary Dentistry 26, 74-81.

3. Hardy, B.T., de Brito Galvao, J.F., Green, T.A et al (2015). Treatment of ionised hypercalcemia in 12 cats (2006-2008) using PO-administered alendronate. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 29, 200-206.

Case Advice or Arranging a Referral

If you are a veterinary professional and would like to discuss a case with one of our team, or require pre-referral advice about a patient, please call 01883 741449. Alternatively, to refer a case, please use the online referral form