Internal Medicine

Diagnosing hyperadrenocorticism with confidence

Canine hyperadrenocorticism:

How to not stress about the diagnosis

- Identify other diseases before endocrine testing

- ACTH (Synacthen®) is not necessary to diagnose the condition in many dogs

- UCCR is rarely used to confirm the disease

- Beware the ‘unwell’ dogs with hyperadrenocorticism

Getting started

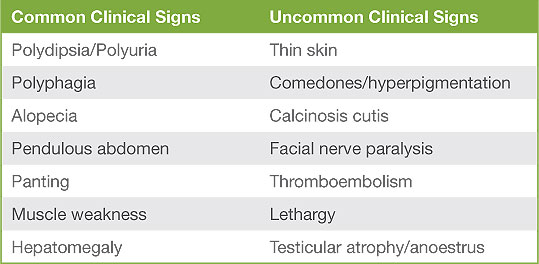

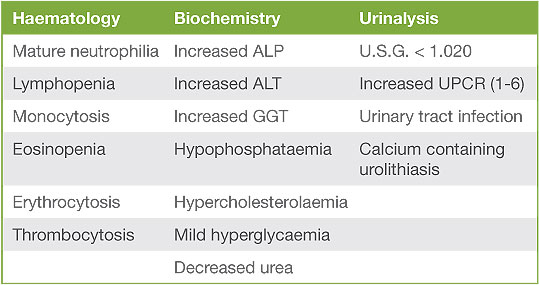

Making a confident diagnosis of canine hyperadrenocorticism (HAC) can be a challenge. A thorough history and physical examination is the first and most important step; testing should only be performed in the setting of compatible clinical sign(s). Common and uncommon clinical signs are shown in table 1 and expected clincopathological alterations are shown in table 2. The more compatible abnormalities present, the higher the likelihood of HAC. Conversely the presence of incompatible abnormalities such as vomiting or anorexia significantly reduces the likelihood of the disease and indeed testing for the condition should be reconsidered.

Diagnostic imaging should be performed ideally before specific endocrine testing. Radiographs of the abdomen can identify hepatomegaly. A calcified adrenal mass can occur, however they are only seen in 50% of ADH cases.

Adrenal ultrasound is more informative but identification requires practice. In PDH the adrenal glands are typically symmetrically enlarged and normal in shape, size and echogenicity (figure 1). In ADH, normally a unilateral adrenal mass is detected, which is unusual in shape and echogenicity (figure 2), with the contralateral adrenal gland typically small. Adrenal gland masses can also be invading or compressing adjacent structures such as the caudal vena cava.

Table 1: Clinical signs of HAC

Table 2: Clinicopathological abnormalities

Endocrine Testing

There are several different tests available, which can confuse and frustrate in equal measure. When selecting a test or tests to perform, it is important to consider their varying sensitivities and specificities, which are in turn influenced by the likelihood of HAC in that particular population, concurrent medication, acute stress and disease. Concurrent drugs such as glucocorticoids (including topical medication) can affect the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

Low dose dexamethasone suppression test (LDDST)

The LDDST is very sensitive (90-95%) and moderately specific (44-73%). False positives can occur in patients with non-adrenal illness and this test should be reserved for those cases with a reasonable index of suspicion, after other non-adrenal illnesses have been excluded. If a patient is concurrently unwell, testing should be delayed until recovery. Even acute mild stress (such as an ultrasound) could affect the results. The diagnosis is based on the cortisol result obtained 8 hours after administration of dexamethasone, and the cut-off value varies between laboratories and depends to some extent on the severity of the clinical signs and other clinic-pathological tests. Occasionally an “inverse” pattern is seen, when the result obtained at 3 or 4 hours after administration is above the cut-off for diagnosis but the result at 8 hours is below. This pattern is suspicious for HAC, but further testing (i.e. repeating the LDDST or pursuing alternative tests) is recommended.

ACTH stimulation

The ACTH stimulation test is the least sensitive (between 60-85%) and most specific (59-93%) test. False positives are not as frequently encountered as with the LDDST, tending to occur with more severe non-adrenal illness (e.g. diabetic ketoacidosis). Acute stress is less likely to affect the results. In ADH the sensitivity is lower when compared to PDH, however when the test is performed clinically, this distinction may not yet have been made. If a dog has a positive or in some circumstances a borderline result, with compatible clinical signs and results of previous investigations (including exclusion of other conditions), it is extremely likely to have the HAC.

Urine cortisol to creatinine ratio

The UCCR is the most sensitive test (75-100%); however it lacks specificity (20-25%). Although the UCCR will be positive in the majority of dogs with HAC, dogs with other unrelated non-adrenal illnesses and experiencing acute stress (such as examination or hospitalisation) can also test positive. To reduce the risk of a misdiagnosis, it is best to perform the test on two or even three morning samples collected at home and pooled in equal volumes. Given the problems encountered with the test, the UCCR is used by the authors primarily to exclude HAC.

Beware the ‘unwell’ hyperadrenocorticoid patient

Before reaching a diagnosis of HAC it is essential to exclude other conditions. Most dogs with the condition are well however occasionally patients can be unwell, directly attributable to the disease. For example some patients with a pituitary macroadenoma can have reduced appetite or mentation. Dogs can also become hyper-coaguable, with some developing thromboembolism. Due to the acute metabolic stress this group of patients may be experiencing, interpretation of endocrine test results is fraught with difficulty. These scenarios are not common and investigation and indeed treatment for HAC, even if it is suspected to be the underlying aetiology, should be withheld until stability has been achieved.

Conclusions

Thorough case evaluation and a logical work-up should ensure that the diagnosis of HAC is achieved without stress. The treatment of HAC, whether medical or surgical, can be costly and a complete investigation before starting this treatment does not add significantly to this when compared to the costs of misdiagnosis.

- Behrend EN, Kooistra HS, Nelson CE, et al: Diagnosis of spontaneous canine hyperadrenocorticism: 2012 ACVIM consensus statement (small animal). J Vet Intern Med, 27:1292-1304, 2013.

- Gilor C, Graves TK : Interpretation of laboratory tests for canine Cushing’s syndrome. Top Companion Anim Med, 26: 98-108, 2011.

- Herrtage ME, Ramsey IK : Canine hyperadrenocorticism, in Mooney CT, Peterson ME (ed): BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Endocrinology 4th Edn. BSAVA Publications, Gloucester, 2012.

- Kaplan AJ, Peterson ME, Kemppainen RJ: Effects of disease on the results of diagnostic tests for use in detecting hyperadrenocorticism in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 211:322-325, 1997.

- Kooistra HS, Galac S: Recent advances in the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome in dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 40:259-267, 2010.

- May ER, Frank LA, Hnilica KA, et al: Effects of a mock ultrasonographic procedure on cortisol concentrations during low-dose dexamethasone suppression testing in clinically normal dogs. Am J Vet Res 65:267-270, 2004.

- Melian C, Perez-Alenza MD, Peterson ME: Hyperadrenocortisim in dogs, in Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC (eds): Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, Diseases of the dog and the cat, ed 7. Elsevier, 2011.

- Peterson ME: Diagnosis of hyperadrenocorticism in dogs. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract, 22:2-11, 2007.

Figure 1: Abdominal ultrasound showing adrenomegaly in a dog with pituitary dependent HAC.

Figure 2: Abdominal ultrasound showing right sided adrenal mass in a dog with adrenal dependent HAC.

Case Advice or Arranging a Referral

If you are a veterinary professional and would like to discuss a case with one of our team, or require pre-referral advice about a patient, please call 01883 741449. Alternatively, to refer a case, please use the online referral form