What are anal sac tumours?

The anal sacs are two small glands that sit either side of the anus (back passage) under the tail. They produce a strong-smelling secretion which is emptied onto the faeces (stools).

Tumours (growths) may develop from the lining cells of these glands. These tumours are relatively uncommon in dogs, representing approximately 2% of all skin tumours, and they are very rare in cats. Anal sac tumours tend to be malignant and invade into tissues outside of the anal sac, and they also have the potential to spread to other areas, including the lymph nodes (‘lymph glands’) under the spine and the lungs. Between 50 and 80% of dogs have evidence of tumour spread at the time of diagnosis, even though in some of these animals the primary (original) tumour is small (less than 1cm across).

Anal sac tumours may be suspected or identified in the following ways:

- The tumour may be noted as an incidental finding during a routine examination, especially when an internal rectal examination is performed

- A lump or mass close to the anus is noticed or can be felt, e.g. during grooming

- A mass close to the anus causes irritation or bleeding in this area

- A large mass close to the anus or enlargement of the lymph nodes in the pelvis may cause difficulty in passing faeces and constipation

- Some tumours cause an elevation in the levels of calcium in the blood, and the clinical signs related to this abnormality (weakness, drinking more) are noticed first by the owner

An elevated blood calcium level is seen in 27 to 90% of animals with anal sac tumours. The blood calcium level tends to fall with successful treatment, and a recurrence of the high blood calcium level often indicates recurrence of the tumour.

A large anal sac carcinoma. This patient had a high blood calcium level as a result of the tumour

Diagnostic testing

When this tumour is suspected, a rectal examination and a biopsy are performed to confirm the diagnosis. Other diagnostic tests are also performed to determine which sites of the body are affected and to identify whether the blood calcium level is elevated.

These tests include:

- Blood samples for haematology (looking at red and white blood cells) and biochemistry (looking at various factors including blood calcium levels and internal organ function)

- Urine analysis

- CT scan or X-ray examination of the chest

- CT scan, X-ray, or ultrasound examination of the abdomen (tummy)

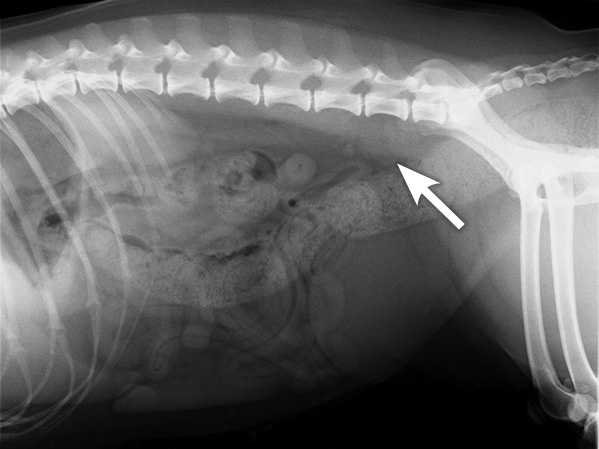

X-ray of a patient with mildly enlarged lymph nodes under the spine (arrow)

Treatment options

The treatment of anal sac tumours has a number of aims:

1. Initial management of high blood calcium levels in certain patients

2. Controlling the tumour at the primary (original) site in the anal sac

3. Controlling the tumour if it has spread to the lymph nodes

4. Delaying or preventing tumour spread in the long term

5. Controlling the progression of advanced cancer spread (metastasis)

- Initial management of high blood calcium levels in certain patients

High blood calcium can have a number of adverse effects on the body and increases the risk when giving a general anaesthetic. The problem is treated initially with intravenous fluids (a ‘drip’) and drugs to encourage the calcium to be flushed out through the kidneys. Once the blood calcium level has been reduced with medical therapy, surgical removal of the tumour at the primary site and in the lymph nodes will prevent the calcium level rising again. - Controlling the tumour at the primary (original) site in the anal sac

This is best performed by removing the tumour surgically, although this can be difficult for large tumours in this area. Surgery can be followed by radiotherapy if not all the tumour can be removed, although radiotherapy has the potential for causing side-effects. - Controlling the tumour if it has spread to the lymph nodes (‘lymph glands’)

If the tumour has spread to the lymph nodes, the lymph nodes may be removed surgically, or included in the radiotherapy field, if radiotherapy is to be used as a treatment option. - Delaying or preventing tumour spread in the long term

The role of chemotherapy in the treatment of anal sac tumours is not clear cut. Animals with advanced disease, where the tumour has already spread and cannot be managed with surgery, tend to do better if chemotherapy is given. However, in cases which can have all detectable tumour removed surgically, it remains to be shown whether invisibly small microscopic tumour tissue is best managed by chemotherapy or simply by close monitoring and possible further surgery in the future. - Controlling the progression of advanced cancer spread (metastasis)

Here at North Downs Specialist Referrals, we have seen remarkable success in the treatment of advanced anal sac tumour patients using treatment which is designed to prevent the cancer from inducing the formation of new blood vessels. This approach to therapy effectively targets the cancer, whilst sparing the non-cancerous tissues, because non-cancerous tissues are not growing and therefore do not need to grow a new blood supply to support their growth. Using this treatment, patients who would previously have had a life expectancy of as little as ten weeks, are living for one to two years.

X-rays of a patient’s lungs once spread of the cancer was noted in July 2014 and taken in February 2016 when she still remained alert and active despite slow progression of her cancer. The cancer progression is evident; the miracle is that these changes would historically have happened in only ten weeks.

Outcome and prognosis (outlook)

Anal sac tumours are malignant and have the potential to spread. Many animals are not completely cured of their tumour with treatment. However, with appropriate treatment, we can improve the quality of life for our patients for a long period of time.

The average survival time for dogs with anal sac tumours is dependent on the extent of the cancer problem when they are first seen by the Specialist. For dogs with cancer limited to the anal sac site, a curative outcome is possible. Average life expectancy is almost four years. For dogs with cancer spread to the lymph nodes average life expectancy following appropriate therapy is stated as being between 12 and 24 months. However, with the advent of new knowledge, and with the application of novel therapies, patients can and do live for many years.

The outcome tends to be poorer for patients with the following:

- High blood calcium

- Large tumours, particularly greater than 10cm across

- Tumour spread to the lymph nodes and lungs

However, even in the presence of these factors, effective therapies to improve the quality of life of such patients can still be offered.

If you have any queries or concerns, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Arranging a referral for your pet

If you would like to refer your pet to see one of our Specialists please visit our Arranging a Referral page.