Dogs and cats can develop or acquire severe problems that affect their limbs, such as traumatic injuries, tumours and deformities. Wherever possible such conditions are treated so that limb function is restored to as near normal as possible, for example by repairing a fracture or a dislocated joint. Occasionally this is not possible due the nature or severity of the condition and other solutions need to be considered, namely amputation or, alternatively, a limb sparing procedure.

Amputation

Some dogs and cats may be able to function satisfactorily with three limbs and thus amputation may be an option in these cases. These patients need to be carefully assessed to ensure their other limbs are sufficiently healthy to enable pain-free mobility following amputation. Smaller animals tend to cope better than larger ones.

Limb sparing procedures

Some dogs and cats may be suitable for a limb sparing procedure that aims to maintain limb function rather than amputating the limb. Limb sparing operations generally sacrifice the normal function of a joint in the limb. Fusion (arthrodesis) of a joint is generally necessary, although occasionally the joint (for example the hip or knee) can be replaced. Limb sparing procedures can be life-saving in some patients where the alternative of amputation is not an option.

What types of conditions may be managed by a limb sparing procedure?

There are number of conditions particularly affecting the bones and joints that may be managed by a limb sparing procedure. Traumatic injuries (such as severe fractures and dislocations), tumours (cancer) and limb deformities are the most common.

Before a limb sparing operation is considered it is important that the condition being treated is accurately diagnosed. This will generally necessitate investigations, such as X-rays or more advanced imaging, for example a CT scan. Other tests, such as a biopsy, may also be necessary.

What does limb sparing surgery involve?

Wherever possible, limb sparing surgery is performed in a single operation. Occasionally more than one operation is necessary, for example when a limb is being lengthened. Where limb sparing surgery is being performed to manage a tumour (cancer) additional therapy, such as chemotherapy, may be necessary.

Limb sparing surgery is undoubtedly a major undertaking. We will be pleased to give as much help and support as possible if you decide to give your pet the opportunity of such surgery. The following are examples of limb sparing procedures that were a better option than amputation in these dogs and cat.

Case 1

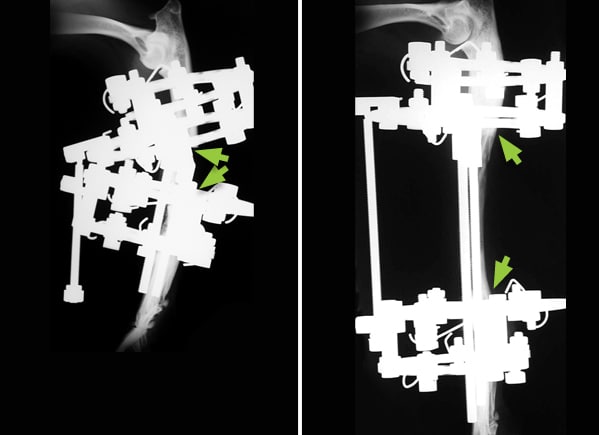

A Boxer pup with a shortened, deformed right forelimb due to one the forearm bones (the radius) not forming during development, a condition known as radial agenesis (arrow shows where the radius should be). Only the ulnar bone is present. As a result the forearm is short and the paw has collapsed inwardly due to a lack of support.

In the first operation the paw was straightened and fused to the ulnar bone. In the second operation the ulnar bone was lengthened (compare the distance between the arrows in the two X-rays) using pins, rings and threaded connecting bars.

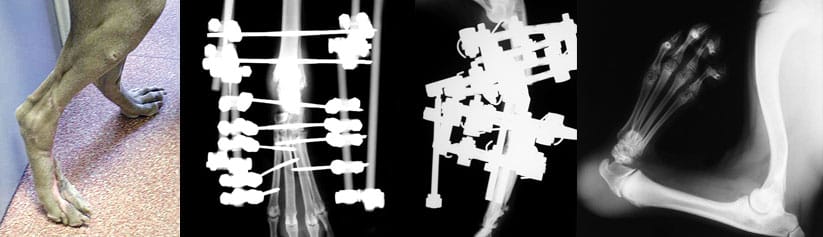

X-ray and photograph of the same Boxer as an adult dog, showing the straightened and lengthened limb. There is no movement in the carpus (wrist joint) because it has been fused.

Case 2

A West Highland White Terrier pup with a deformed left forelimb. The paw is not connected to the radius which is the principle weight bearing bone in the forearm. As a result the paw is collapsing to the outside of the limb. A condition known as ‘ectrodactyly’.

X-ray and photograph of the same West Highland White Terrier as an adult dog, showing how the paw has been transposed from the ulnar bone and fused to the radius.

Case 3

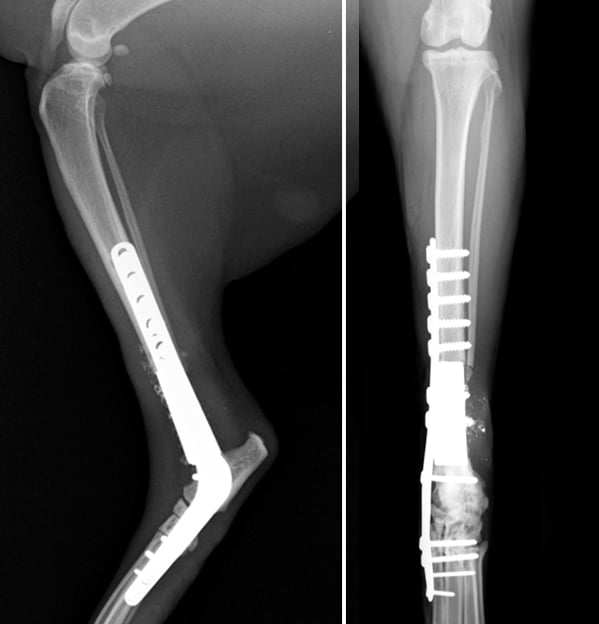

This dog has a slow growing tumour affecting the radial bone just above the carpal joint (wrist) (arrows). The tumour has been removed and the gap packed with a bone graft and supported with two plates and multiple screws. It has been necessary to fuse the carpal joint.

The tumour has been removed and the gap packed with a bone graft and supported with two plates and multiple screws. It has been necessary to fuse the carpal joint.

Case 4

This cat has a benign tumour affecting the tibial bone just above the hock joint (ankle) (arrows).

The tumour has been removed and the gap filled with a metal (tantalum) prosthesis and supported with a specially designed curved plate. It has been necessary to fuse the hock joint.

Case 5

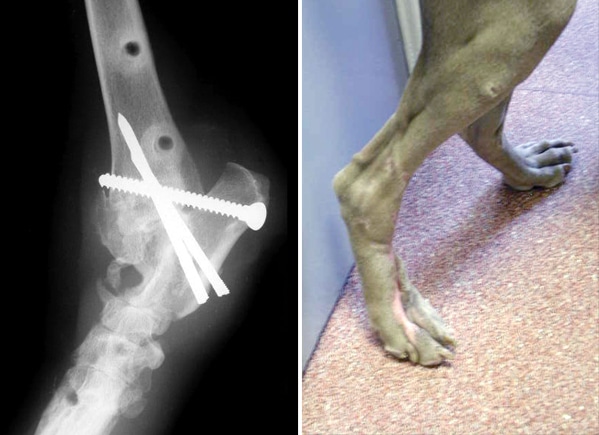

This Weimaraner was hit by a car and sustained multiple fractures of the tarsal joint (the ankle) in addition to severe skin injuries. In two operations the joint was fused using multiple pins that penetrated the skin and were attached to connecting bars on the outside and inside of the limb (an external skeletal fixator).

X-ray and photograph of the same Weimeraner one year after the injury, showing the fused tarsal joint (arrow) with remaining metal implants and residual scars on the paw.

Arranging a referral for your pet

If you would like to refer your pet to see one of our Specialists please visit our Arranging a Referral page.