What is osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis is a very common problem in small animals, as it is in humans. It has been estimated that around 30-50% of dogs and cats will be affected by osteoarthritis at some point in their lives. The condition causes long term degeneration of joints and involves many tissues including cartilage (the white, shiny, low-friction joint surfaces), bone under the cartilage, joint capsule and fluid in the joint (synovial fluid).

Unlike humans where osteoarthritis is usually related to ageing and ‘wear and tear’ of joints, osteoarthritis in dogs usually has a specific underlying cause and is therefore often seen earlier in life. Underlying causes can include developmental conditions such as elbow dysplasia or hip dysplasia, ligament rupture and traumatic problems such as broken bones involving a joint e.g. humeral condylar fractures. Cats are more commonly affected by ‘wear and tear’ and consequently tend to be affected later in life compared to dogs.

What are the signs of osteoarthritis?

The key signs or symptoms of osteoarthritis are stiffness, lameness and pain. Stiffness and lameness are often particularly evident after a period of rest, especially if there has been previous exercise. The stiffness often ‘warms out’ after a few minutes. Joint pain associated with osteoarthritis may manifest in a number of ways, including moaning, restless sleep and altered behaviour (including aggression). Reluctance to climb, jump and exercise are additional features.

Are all animals with osteoarthritis in pain and lame?

Once osteoarthritis has started in a joint it cannot be cured and will affect an animal for the rest of his or her life. However, the osteoarthritis can be broadly divided into two forms (1) chronic active osteoarthritis which causes pain and lameness and (2) chronic silent osteoarthritis which may cause stiffness but not pain or lameness. It is possible for a dog or cat to have the silent form of osteoarthritis for long periods with occasional bouts of the active form which may develop, for example, due to over-exercising and spraining the osteoarthritic joint.

How is osteoarthritis diagnosed?

Joints affected with osteoarthritis are often thickened with a restricted range of movement and muscles on the affected limb (leg) are invariably wasted or reduced in size (atrophied). Detecting evidence of pain on manipulation of arthritic joints is an important feature that helps distinguish the active and silent forms of the disease. Radiographs (X-rays) are the most common method of diagnosing osteoarthritis and ruling out other possible causes of joint pain and lameness. Radiographic features typically include the formation of abnormal bone around the joint. As in people more advanced imaging, such as MRI scanning, CT scans and ultrasound scans, is occasionally necessary to investigate osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy is a technique that enables inspection of the inside of joints with a camera and may be indicated in select cases, for example to detect torn ligaments. Collection and analysis of joint fluid (synovial) can be an important investigation in some cases to rule out possible infection and rheumatoid-like conditions.

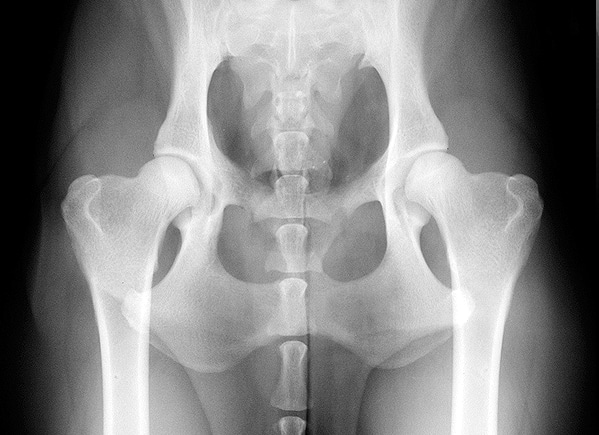

X-ray showing normal hip joints

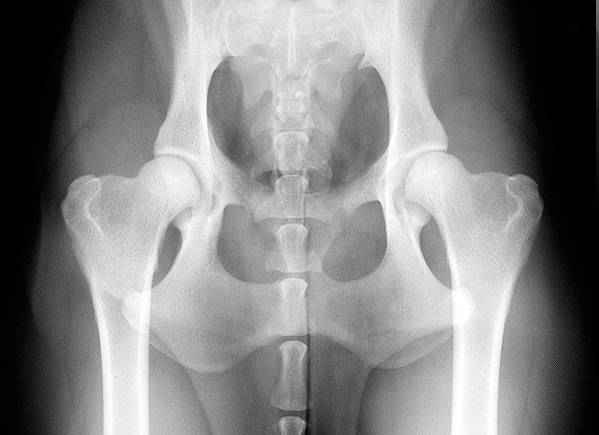

X-ray showing hips with osteoarthritis (arrows)

How is osteoarthritis treated?

Since osteoarthritis cannot be easily cured, the aim of treatment is to convert chronic active osteoarthritis into chronic silent osteoarthritis. There is no single approach to treatment that is successful in every case, and most dogs and cats need a multi-modal approach.

- Since osteoarthritis can be painful, painkillers are usually prescribed. In the long term these can often be reduced or discontinued, although in some animals long term medication is needed. Although long term medication can have a risk of side effects, this risk must be balanced against recurrence of pain from the osteoarthritis if the medication is not given.

- Exercise levels are very important. Initially when a joint is painful it is necessary to decrease exercise, often to just short walks on the lead. In the long term, it is very important to gradually increase exercise as much as possible. This allows pets to remain fit and active and enjoy a good quality of life. However, excessive activity must be avoided since this could cause pain to recur. There is no golden rule as to how much exercise an animal with osteoarthritis can have, since all patients are different; instead, exercise levels need to be tailored to the individual animal.

- Weight control is also very important. Pets that are an ideal weight have fewer painful episodes and less progression of osteoarthritis than overweight animals. Prescription diets may be needed in some animals to help with weight loss.

- Long term food supplements such as glucosamine, chondroitin and green lipped muscle extract have been proposed to help reduce the progression of osteoarthritis in the joint. Whilst these products are very popular and are safe, it should be borne in mind that there is very little proof of their effectiveness.

- Foods containing omega-3-fatty acids can have a natural anti-inflammatory action which may help to relieve discomfort associated with osteoarthritis. Supplements (such as evening primrose oil) or special prescription diets can be used.

- Physiotherapy and hydrotherapy can be useful in some pets to help maintain fitness and muscle mass. These therapies need to be discussed carefully with your vet before being started, to avoid making painful joints worse. TOP What happens if my pet seems to be getting worse despite the treatment? Because osteoarthritis is a waxing and waning disease, animals can have good days and bad days. If symptoms of pain seem to worsen, it may be necessary to increase painkillers and cut back on exercise for a while. In some animals, treatments may need to be changed and different medications used.

What if none of the treatments seems to be working?

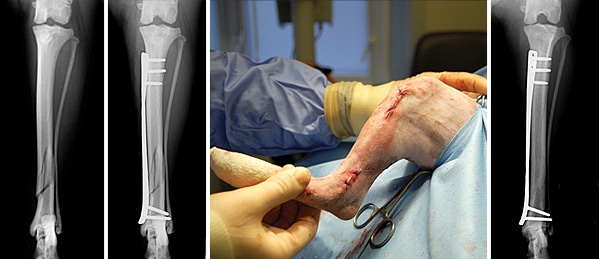

In some animals the osteoarthritis can be so severe that medications are ineffective. In these cases salvage surgery may be considered. Arthrodesis, or fusion of a joint, is often performed for the carpus (wrist) or tarsus (ankle). Joint fusion is occasionally performed for other joints such as the shoulder, elbow or knee. In the hip, the painful ball part of the joint can be removed, an operation called an excision arthroplasty. For the hip, knee and elbow total joint replacement surgery can be considered. These are relatively big operations but animals can regain excellent, pain-free use of a limb and have a very good quality of life, especially following hip and knee replacements.

We are always happy to discuss any aspects of a case with you or your vet prior to referral. If you have any questions or concerns please contact us.

Arranging a referral for your pet

If you would like to refer your pet to see one of our Specialists please visit our Arranging a Referral page.