It is not uncommon for cats of all ages to suffer from oral inflammation, and sometimes it can be hard to distinguish between gingivitis and gingivostomatitis. Cats can also be asymptomatic carriers of calicivirus, which can confuse the diagnostic pathway. How do we tell the diseases apart, and what are the best treatments?

Gingivitis is the first stage of periodontal disease. It is characterised by inflammation of the gingiva. This can be focal (affecting one area in the mouth), or generalised (affecting all of the gingiva). The inflammation starts at the margin of the gingiva and can progress to affect the whole of the attached gingiva when severe.

By definition, gingivostomatitis not only involves gingival inflammation, but an extension of the inflammation across the mucogingival junction onto the adjacent oral mucosa (stomatitis). The diseases however, are distinctly different, as we will see below.

Anatomy Refresher

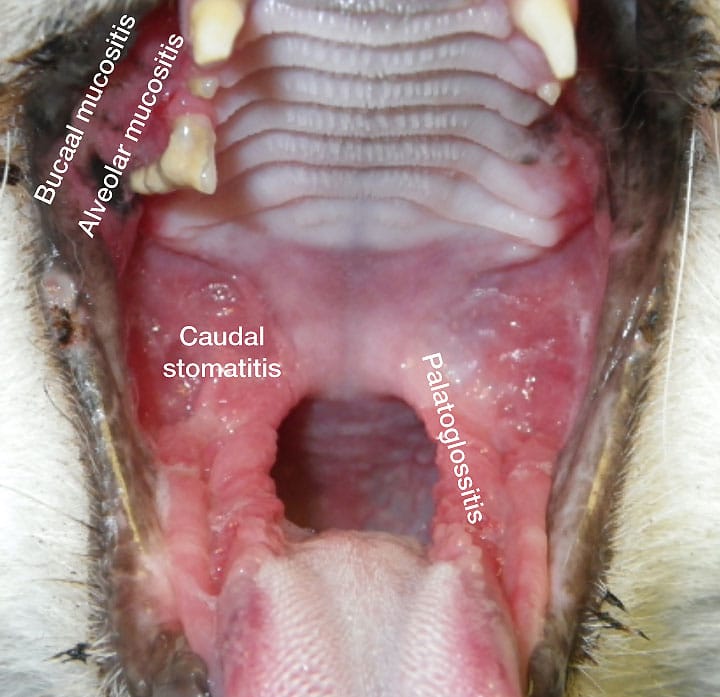

To understand the difference in these diseases, it is a good idea to recap our knowledge of anatomy. The gingiva is the structure immediately attached to the tooth surface, and adjacent alveolar bone. There is a free margin, a sulcus (which has a normal depth of <1mm in the cat) and the attached gingiva, which is firmly attached to underlying bone. There is then a transition to oral mucosa, and this junction is known as the mucogingival junction. It is quite subtle in the cat compared to the dog, but is definitely present. The alveolar mucosa then covers the alveolar bone, and as the oral mucosa reflects around the line lips and cheeks it becomes known as labial or buccal mucosa. The entrance to the oropharynx is bordered by the palatoglossal folds. The area lateral to this has in the past incorrectly referred to as the fauces. This anatomical area does not have an anatomical name, and therefore if there is inflammation here it is referred to as caudal stomatitis. The isthmus of the fauces is the space between soft palate, tongue and palatoglossal folds. The fauces form the part of the pharynx bounded laterally by the palatine tonsil and its surrounding structures.1

In Figure 1, we can see that there is generalised gingivitis in this patient, with inflammation affecting much of the attached gingiva, but not crossing the mucogingival junction, which is highlighted in green in Figure 2.

Inflammation of the oral mucosa can therefore have various names, depending on the location. Stomatitis refers to inflammation of any part of the oral mucosa. See Figure 3.

Periodontal Disease

Periodontal disease is caused by plaque bacteria, which form a biofilm adherent to the tooth surface. There are bacteria coating all gingival and mucosal surfaces in the mouth, however the epithelial nature of these tissues ensures a constant turnover of the surface layer of cells. Compare this to the enamel covering the teeth, which is a non-changing structure. Plaque is an invisible film of bacteria and may only be obvious when highlighted with plaque-disclosing solutions. As plaque builds up on the tooth surface and enters the gingival sulcus it incites an inflammatory reaction in the gingiva, which we recognise as gingivitis. This, in itself, is non-painful. The inflammation is also reversible if plaque is removed (either professionally, or by tooth brushing at home). In young cats, a hyperplastic gingivitis may be stimulated. In this disease, there is either a generalised or focal enlargement of the gingiva (See Figure 4). This in turn collects more plaque bacteria under the flap of tissue (known as a pseudopocket), leading to further inflammation.

Calculus (or tartar) is simply mineralised plaque. It is not in itself pathogenic, and the severity of disease should not be judged by calculus levels.

The course of the disease is then largely determined not only by the bacterial population2, but by the immune and inflammatory response of the cat, which is of course driven by genes. If the disease advances, it is termed periodontitis. This is characterised by attachment loss for the tooth, which is predominantly characterised by horizontal alveolar bone loss, and often associated with tooth resorption (type 1 or inflammatory resorption).3

Mobility of teeth and resorption are both associated with pain. This can be seen as a disease in young animals, known as juvenile periodontitis. It tends to be aggressive and rapidly progressive, and is often see in Oriental and Maine Coons, but can be seen in Domestic Shorthair cats or any breed.

Feline Chronic Gingivostomatitis (FCGS)

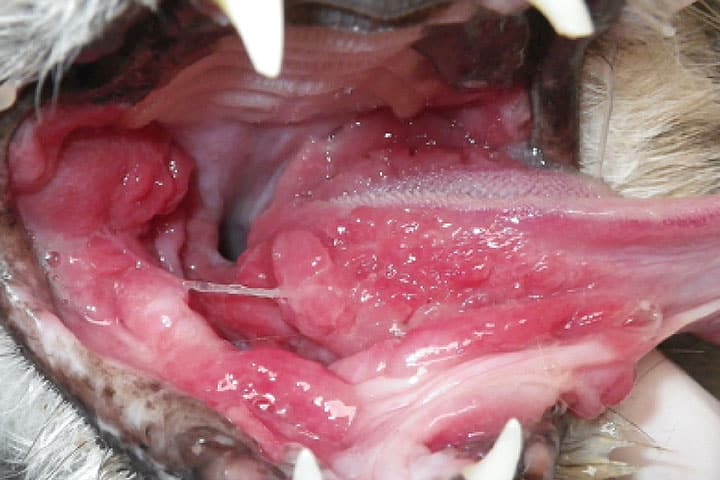

FCGS is commonly encountered in general practice and is a frustrating disease to treat because it is not fully understood. A good review article has been published by Lee et al.4 It is essentially an immune-mediated, inflammatory mucosal disease characterised by ulceration and proliferation of tissue. Caudal stomatitis, alveolar and buccal stomatitis plus palatoglossitis characterise the disease (see Figure 3). Sometimes the proliferative nature can affect the sub-lingual area (Figure 5).

Due to the ulcerative nature, this is an intensely painful disease. It is thought to be an aberrant immune response to a variety of oral antigens, including plaque bacteria. Feline calicivirus, Feline Herpes Virus-1, FIV, and FeLV have been implicated in FCGS, but none have been proved to be causative. Calicivirus seems to have the most evidence of being associated with FCGS, and the majority of cats with the disease will test positive via PCR analysis.5 However, it is not causative for the disease. Moreover, there is no evidence that the viral load is linked to the severity of disease, nor the outcome after treatment.5

Cats that suffer from acute calicivirus infections show upper respiratory signs, conjunctivitis and oral ulceration, typically of the hard palate and tongue. There is no evidence that these patients will later suffer from FCGS.

Healthy cats can be carriers of calicivirus, particularly if from a multi-cat environment.6,7

Stress may play a role in the multi-factorial nature of FCGS, with a multi-cat household appearing to act as a risk factor.8

To complicate things, cats with FCGS tend to have clinical and radiographic signs of periodontitis as well as inflammatory root resorption.9 Diagnosis must therefore include a thorough oral and dental examination under anaesthesia, including full mouth dental radiography.

So, how do we tell the two diseases apart?

By obtaining a thorough history, and performing a diligent physical examination, we can often come to a tentative diagnosis.

- Cats with gingivitis tend to behave quite normally, they eat well and groom themselves, going about normal activities. It is often an incidental finding, with perhaps the only complaint from the owner being halitosis. They maintain a normal bodyweight. If the cat is suffering from periodontitis and resorption however, they may show obvious signs of pain. This can present as a reluctance for a particular food type, or chewing on one side of the mouth, or dropping food. Cats with FCGS on the other hand tend to lose weight due to hyporexia. They are hungry, but find chewing and swallowing food painful, so lose weight. They will often not groom properly so have an untidy, greasy hair-coat. Owners are often very aware their cat has a problem and will present the cat for this.

- By performing a careful oral examination under anaesthesia, we can determine the extent of inflammation in the oral cavity. Is there caudal stomatitis and palatoglossitis to suggest FCGS, or is the inflammation restricted to the gingiva? Full mouth dental radiography should be included for all patients, to diagnose any periodontitis and tooth resorption.9

How do we treat these diseases?

Gingivitis The patient should be examined under general anaesthesia, and full mouth dental radiographs obtained. Plaque and caluclus deposits are removed by ultrasonic scaling and polishing. Any hyerplastic gingiva should be removed by gingivectomy, so the gingival margin is returned to normal levels. A homecare regimen should be instituted to control plaque re-accumulation, ideally by daily tooth brushing. A chlorhexidine paste or gel can be used (such as PetDent gel). This is notoriously difficult in feline patients, and so regular checks should be performed. Progression to periodontitis could be anticipated, which would necessitate extraction therapy.

Chronic Gingivostomatitis Medical therapy alone is unlikely to provide a favourable long-term outcome.4 Effective treatment therefore relies on surgery with tooth extractions, with or without additional medical therapy. Regardless of treatment approach, adequate analgesia is paramount.

Treatment aims to control the oral pathogens to allow the cat’s immune response to shift to a more favourable one. Medical therapy alone is unlikely to control or cure this condition. A strong analgesic plan is mandatory, which may include NSAIDs, gabapentin and buprenorphine.10

A few studies have shown that partial- (all premolar and molar teeth) or full-mouth extractions can give the best long-term results, with roughly 70-80% cats showing significant improvement or resolution, and 20-30% cats showing minimal improvement.11,12,13 It is worth noting that the best evidence suggests partial mouth extractions (including canines and incisors if there are additional reasons for extracting these teeth).11 These should be performed competently, under radiographic control with no retention of roots or root remnants. Referral to a veterinary dentist should be considered early on in the disease process.

In patients that require ongoing medical therapy, there are various options. Recombinant feline omega interferon was noted to be as effective as prednisolone in a randomised, controlled clinical trial, and may also help to control calicivirus replication.14,15 Cyclosporine has also been studied in cats non-responsive to extractions and may allow remission in 50% patients.16 This is less likely to be effective though, if the cat has already received prednisolone.

Prednisolone is a potent anti-inflammatory and may support resolution in some cats.14 Due to the risk of side effects, doses should be tapered to the least effective dose, and stopped when possible. They may be a solution for client with cost concerns if extractions have not helped.

Pilot studies have explored the use of autologous or allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells shows encouraging results. However given the complexity of the acquisition, production and transfusion of stem cells, the treatment is not likely to be available to general practitioners for the foreseeable future. Recent research by the same group has shown there is no benefit to stem cell therapy attempted prior to extractions.17,18,19

A systematic review of the literature regarding the therapeutic management of gingivostomatitis has been published by Win

Due to the ulcerative nature, this is an intensely painful disease. It is thought to be an aberrant immune response to a variety of oral antigens, including plaque bacteria. Feline calicivirus, Feline Herpes Virus-1, FIV, and FeLV have been implicated in FCGS, but none have been proved to be causative. Calicivirus seems to have the most evidence of being associated with FCGS, and the majority of cats with the disease will test positive via PCR analysis.5 However, it is not causative for the disease. Moreover, there is no evidence that the viral load is linked to the severity of disease, nor the outcome after treatment.5

Cats that suffer from acute calicivirus infections show upper respiratory signs, conjunctivitis and oral ulceration, typically of the hard palate and tongue. There is no evidence that these patients will later suffer from FCGS.

Healthy cats can be carriers of calicivirus, particularly if from a multi-cat environment.6,7

Stress may play a role in the multi-factorial nature of FCGS, with a multi-cat household appearing to act as a risk factor.8

To complicate things, cats with FCGS tend to have clinical and radiographic signs of periodontitis as well as inflammatory root resorption.9 Diagnosis must therefore include a thorough oral and dental examination under anaesthesia, including full mouth dental radiography.

So, how do we tell the two diseases apart?

By obtaining a thorough history, and performing a diligent physical examination, we can often come to a tentative diagnosis.

- Cats with gingivitis tend to behave quite normally, they eat well and groom themselves, going about normal activities. It is often an incidental finding, with perhaps the only complaint from the owner being halitosis. They maintain a normal bodyweight. If the cat is suffering from periodontitis and resorption however, they may show obvious signs of pain. This can present as a reluctance for a particular food type, or chewing on one side of the mouth, or dropping food. Cats with FCGS on the other hand tend to lose weight due to hyporexia. They are hungry, but find chewing and swallowing food painful, so lose weight. They will often not groom properly so have an untidy, greasy hair-coat. Owners are often very aware their cat has a problem and will present the cat for this.

- By performing a careful oral examination under anaesthesia, we can determine the extent of inflammation in the oral cavity. Is there caudal stomatitis and palatoglossitis to suggest FCGS, or is the inflammation restricted to the gingiva? Full mouth dental radiography should be included for all patients, to diagnose any periodontitis and tooth resorption.9

How do we treat these diseases?

Gingivitis The patient should be examined under general anaesthesia, and full mouth dental radiographs obtained. Plaque and caluclus deposits are removed by ultrasonic scaling and polishing. Any hyerplastic gingiva should be removed by gingivectomy, so the gingival margin is returned to normal levels. A homecare regimen should be instituted to control plaque re-accumulation, ideally by daily tooth brushing. A chlorhexidine paste or gel can be used (such as PetDent gel). This is notoriously difficult in feline patients, and so regular checks should be performed. Progression to periodontitis could be anticipated, which would necessitate extraction therapy.

Chronic Gingivostomatitis Medical therapy alone is unlikely to provide a favourable long-term outcome.4 Effective treatment therefore relies on surgery with tooth extractions, with or without additional medical therapy. Regardless of treatment approach, adequate analgesia is paramount.

Treatment aims to control the oral pathogens to allow the cat’s immune response to shift to a more favourable one. Medical therapy alone is unlikely to control or cure this condition. A strong analgesic plan is mandatory, which may include NSAIDs, gabapentin and buprenorphine.10

A few studies have shown that partial- (all premolar and molar teeth) or full-mouth extractions can give the best long-term results, with roughly 70-80% cats showing significant improvement or resolution, and 20-30% cats showing minimal improvement.11,12,13 It is worth noting that the best evidence suggests partial mouth extractions (including canines and incisors if there are additional reasons for extracting these teeth).11 These should be performed competently, under radiographic control with no retention of roots or root remnants. Referral to a veterinary dentist should be considered early on in the disease process.

In patients that require ongoing medical therapy, there are various options. Recombinant feline omega interferon was noted to be as effective as prednisolone in a randomised, controlled clinical trial, and may also help to control calicivirus replication.14,15 Cyclosporine has also been studied in cats non-responsive to extractions and may allow remission in 50% patients.16 This is less likely to be effective though, if the cat has already received prednisolone.

Prednisolone is a potent anti-inflammatory and may support resolution in some cats.14 Due to the risk of side effects, doses should be tapered to the least effective dose, and stopped when possible. They may be a solution for client with cost concerns if extractions have not helped.

Pilot studies have explored the use of autologous or allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells shows encouraging results. However given the complexity of the acquisition, production and transfusion of stem cells, the treatment is not likely to be available to general practitioners for the foreseeable future. Recent research by the same group has shown there is no benefit to stem cell therapy attempted prior to extractions.17,18,19

A systematic review of the literature regarding the therapeutic management of gingivostomatitis has been published by Winer et al. as an open access resource.20

er et al. as an open access resource.20

Gingivitis can be distinguished from chronic gingivostomatitis by taking a careful history and performing a thorough oral and dental examination under anaesthesia including dental radiography. Patients with gingivitis require periodontal therapy and implementation of an oral homecare programme, with careful follow-up. Patients diagnosed with chronic gingivostomatitis have the best chances of success if treated early and surgically.

Please do feel free to contact us for specific case advice in feline patients with gingivitis or gingivostomatitis. Email: dentistry@ndsr.co.uk

References:

- Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria, sixth edition. Prepared by the International Committee on Veterinary Gross Anatomical Nomenclature, published by WAVA. 2017. http://www.wava-amav.org/wava-documents.html

- 2 Rodrigues, M.X., Bicalho, R.C., Fiani, N. et al. The subgingival microbial community of feline periodontitis and gingivostomatitis: characterization and comparison between diseased and healthy cats. Sci Rep 9, 12340 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48852-4

- Lommer, M. J., Dr., and Verstraete, F. J. M. (2001). Radiographic patterns of periodontitis in cats: 147 cases (1998–1999). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 218, 2, 230-234, https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.2001.218.230

- Lee, DB, Verstraete FJM, Arzi B. (2020). An Update on Feline Chronic Gingivostomatitis. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice. 50, 5, 973-982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvsm.2020.04.002

- Druet I, Hennet P. (2017) Relationship between Feline calicivirus Load, Oral Lesions, and Outcome in Feline Chronic Gingivostomatitis (Caudal Stomatitis): Retrospective Study in 104 Cats. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 4 https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fvets.2017.00209

- Berger, A., Willi, B., Meli, M.L. et al. (2015) Feline calicivirus and other respiratory pathogens in cats with Feline calicivirus-related symptoms and in clinically healthy cats in Switzerland. BMC Vet Res 11, 282. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-015-0595-2

- Coyne KP, Dawson S, Radford AD, et al. (2006) Long-term analysis of feline calicivirus prevalence and viral shedding patterns in naturally infected colonies of domestic cats. Veterinary Microbiology, 118, (1–2), 12-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.06.026

- Peralta S, Carney PC. (2019) Feline chronic gingivostomatitis is more prevalent in shared households and its risk correlates with the number of cohabiting cats. J Feline Med Surg. 21, 12, 1165-1171. doi: 10.1177/1098612X18823584.

- Farcas, N., Lommer, M. J., Kass, P. H., and Verstraete, F. J. M. (2014). Dental radiographic findings in cats with chronic gingivostomatitis (2002–2012). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 244, 3, 339-345, available from: < https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.244.3.339

- Stathopoulou TR, Kouki M, Pypendop BH, et al. (2018) Evaluation of analgesic effect and absorption of buprenorphine after buccal administration in cats with oral disease. J Feline Med Surg. 20(8),704–10.

- Jennings MW, Lewis JR, Soltero-Rivera MM, et al. (2015) Effect of tooth extraction on sto- matitis in cats: 95 cases (2000-2013). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 246(6):654–60.

- Druet I, Hennet P. (2017) Relationship between feline calicivirus load, oral lesions, and outcome in feline chronic gingivostomatitis (caudal stomatitis): retrospective study in 104 cats. Front Vet Sci 4,209.

- Hennet P. (1997) Chronic gingivo-stomatitis in cats: long-term follow-up of 30 cases treated by dental extractions. J Vet Dent 14:15–21.

- Hennet PR, Camy GA, McGahie DM, et al. (2011) Comparative efficacy of a recombinant feline interferon omega in refractory cases of calicivirus-positive cats with caudal stomatitis: a randomised, multi-centre, controlled, double-blind study in 39 cats. J Feline Med Surg 13(8):577–87.

- Matsumoto H, Teshima T, Iizuka Y, et al. (2018) Evaluation of the efficacy of the subcutaneous low recombinant feline interferon-omega administration protocol for feline chronic gingivitis-stomatitis in feline calicivirus-positive cats. Res Vet Sci 2018;121:53–8.

- Lommer MJ. (2013) Efficacy of cyclosporine for chronic, refractory stomatitis in cats: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded clinical study. J Vet Dent 30(1):8-17.

- Arzi B, Mills-Ko E, Verstraete FJM et al. (2016) Therapeutic efficacy of fresh, autologous mesenchymal stem cells for severe refractory gingivostomatitis in cats. Stem Cells Translational Medicine 5:75–86.

- Arzi B, Clark KC, Sundaram A et al. (2017)Therapeutic efficacy of fresh, allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells for severe refractory feline chronic gingivostomatitis. Stem Cells Translational Medicine 6:1710-1722

- Arzi B, Taechangam N, Lommer MJ, et al. (2020) Stem cell therapy prior to full-mouth tooth extraction lacks substantial clinical efficacy in cats affected by chronic gingivostomatitis. J Feline Med Surg. 23 (6), 604-608 doi: 10.1177/1098612X2096717

- Winer JN, Arzi B, Verstraete FJM. (2016) Therapeutic management of feline chronic gingivostomatitis: A systematic review of the literature. Front Vet Sci 3 (54): 1-10

Case Advice or Arranging a Referral

If you are a veterinary professional and would like to discuss a case with one of our team, or require pre-referral advice about a patient, please call 01883 741449. Alternatively, to refer a case, please use the online referral form

About The Discipline

Dentistry and Oral Surgery

Need case advice or have any questions?

If you have any questions or would like advice on a case please call our dedicated vet line on 01883 741449 and ask to speak to one of our Dentistry and Oral Surgery team.

Advice is freely available, even if the case cannot be referred.