What is a soft tissue sarcoma?

Soft tissue sarcoma (STS) is an umbrella term for a group of tumours that arise from the skin and subcutaneous connective tissues such as:

- fat (liposarcoma)

- fibrous connective tissue (fibrosarcoma)

- nerves (schwannoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour, neurofibrosarcoma)

- ‘pericytes’ of small blood vessels below the skin in the subcutis (hemangiopericytoma).

These tumours are often considered collectively because of their similarity in behaviour. There are some particular subtypes of STS that are not included in this category as they are typically much more aggressive and so must be considered separately (e.g. histiocytic sarcoma, haemangiosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma).

Soft tissue sarcomas may arise from any anatomic site. They tend to appear as if they are discrete and well encapsulated tumours, but are actually usually very invasive into surrounding tissues. As such, local regrowth of the tumour is common after conservative/marginal surgical removal. Soft tissue sarcomas are graded as low, intermediate, or high-grade (sometimes also called 1, 2 or 3 respectively). Most soft tissue sarcomas are low to intermediate grade and have a very low chance of spreading to other places in the body, such as lungs or other organs. High-grade sarcomas have a higher potential for spreading (metastasis) 25-40%

How are soft tissue sarcomas diagnosed?

Diagnosis is suspected on the basis of a relatively firm and relatively immobile mass developing under the skin, particularly the skin of the limbs. Diagnosis requires a sample of the tumour to be examined under the microscope. The simplest test which achieves this is termed a fine needle aspirate. This involves insertion of a hypodermic needle into the mass, suction using a small syringe (‘aspirating cells from the lump into the shaft of the needle) and then expulsion of the cells from the needle onto a glass slide for examination under a microscope. This test is reasonably reliable in soft tissue sarcomas. However, some of these tumours will not give up material readily in response to this test. The result is therefore described as ‘non-diagnostic’.

If a fine needle aspirate is non-diagnostic or if the Specialist considers that additional information about the behaviour of the tumour is required, a biopsy will be recommended. This is often taken using a wide-bore needle (core biopsy) which can often be performed under light sedation; it may be better to perform a surgical biopsy which would require a short general anaesthetic. The biopsy specimen is then submitted for detailed pathology analysis. A diagnosis and a tumour grade can be defined.

What is the treatment?

Surgery

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for soft tissue sarcomas. Surgical excision must be wide and deep in order to remove all of the tumour tissue. When tumours are excised surgically with ‘clean’ surgical margins, no further treatment may be necessary.

If the tumour was not removed with adequate margins as assessed by the pathologist under the microscope when they look at the excised tissue (so called ‘dirty’ margins), a second surgery may be recommended to excise any remaining tumour cells.

Your Specialist may, perhaps surprisingly, sometimes recommend that surgery is performed which will be known not to be curative. The decision-making regarding these tumours can be very complex, but there will be cases where the Specialist considers that the best balance between risks and benefits is actually achieved through a near-complete (as opposed to complete) removal of all tumour. Factors that would be taken into consideration would include: age of the patient; concurrent health issues; grade of the tumour; tumour location; tumour size; rate of tumour growth, and even your Specialist’s own unique experience of this particular family of tumours.

Radiation therapy

Radiotherapy is the use of high dose x-rays directed at a tumour (or area where a tumour has been removed) to kill off cancer cells/cells left over after surgery. In some instances, aggressive surgery is not possible without severe disfigurement or loss of function. In cases where aggressive surgery is not possible, or despite an aggressive resection where tumour cells remain at the margins, radiation therapy can be used to prevent or delay regrowth of the tumour. Radiation therapy is well-tolerated in dogs. Side effects are generally transient and limited to the site where radiation therapy is performed.

Radiation therapy may also be used for large tumours that cannot be surgically removed. Radiation therapy for these tumours is not considered to be as effective as radiation therapy for microscopic disease after surgery. These tumours do not rapidly regress after radiation and ‘control’ may be defined as a slowly-regressing (6 months or longer) tumour, or a tumour that stays stable in size. In some cases, the tumour may regress enough to make surgical removal possible.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is sometimes recommended for high-grade sarcomas to prevent or delay the onset of distant metastases (spread to other sites). Chemotherapy is very well-tolerated in dogs on the whole, but some side effects do occur. Soft tissue sarcoma has been shown to be the tumour, in dogs at least, with the best evidence of a favourable response to a different form of chemotherapy called Metronomic Chemotherapy. Please see the information sheet for further detailed information. However, in brief, metronomic chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcoma typically involves the daily administration of a low dose of an oral chemotherapy agent, cyclophosphamide, with a daily oral anti-inflammatory therapy. Prolonged periods of remission (more than 3 years) can be achieved in patients who undergo incomplete tumour removal followed by metronomic chemotherapy.

What is the prognosis?

Soft tissue sarcomas that are low to intermediate grade and can be removed completely with surgery have an excellent long-term prognosis. Following complete removal, the majority of these tumours will be cured.

Low-grade tumours which are incompletely removed may recur and therefore may benefit from additional surgery, from radiation therapy or from post-operative metronomic chemotherapy.

Intermediate-grade tumours which are incompletely removed will recur in most cases and, if no further action is taken, will probably do so within three to nine months. Additional treatment in the form of surgery, radiation therapy or metronomic chemotherapy is recommended.

For high-grade sarcomas, the long-term prognosis is more guarded. More than half of these cases can be cured by appropriate surgery. However, there remains a risk of metastasis (spread). Chemotherapy (conventional or metronomic chemotherapy) may be indicated to help delay the onset of metastasis. Patients with incompletely excised high-grade soft tissue sarcomas are expected to experience tumour recurrence relatively quickly (two to six months). Radiotherapy and metronomic chemotherapy are both expected to delay this recurrence but neither is expected to prevent it altogether.

Cats versus Dogs

As a general rule, most soft tissue sarcomas in dogs are low-grade whereas most soft tissue sarcomas in cats are high-grade. For dogs, the most common site of tumour development is the lower limb. This location presents the veterinary practitioner with challenges in removal of the mass but the tumour itself is not expected to behave in a particularly aggressive manner. For cats, the most common site of tumour development is the site between the shoulder blades, where injections are typically administered. With appropriate planning and expertise, aggressive tumours in this site can be completely removed resulting in a high probability of a curative outcome. However, without additional post-operative treatment, incomplete removal of these tumours seems to promote the development of an even more aggressive version of the cancer which is much harder to treat and, almost invariably, impossible to cure.

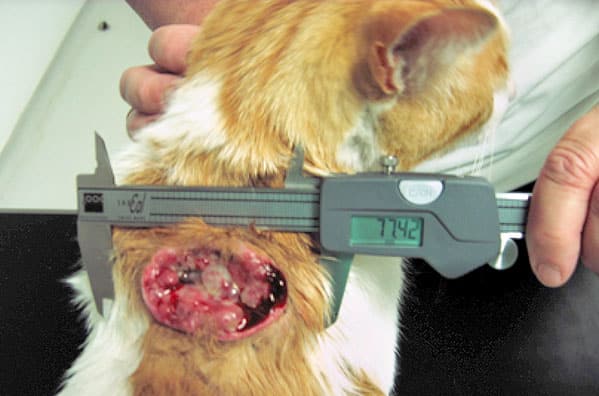

High-grade soft tissue sarcoma between the shoulder blades of a cat. These tumours are potentially very aggressive. Early presentation to an oncology Specialist is strenuously recommended. Appropriate therapy can lead to lengthy periods of remission and even cure. Best outcomes are achieved for patients presented early in the course of disease.

Summary

The best time to treat a soft tissue sarcoma is early in the course of disease. Prompt recognition allows early diagnosis. A well-planned first surgery has the best chance of achieving a curative outcome. Tumours that regrow after an initial surgery are often more aggressive in their behaviour. This makes the potential for metastases greater and reduces our ability to control the tumour locally, even with additional non-surgical therapy.

If you have any queries or concerns, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Arranging a referral for your pet

If you would like to refer your pet to see one of our Specialists please visit our Arranging a Referral page.