The trend for flat-faced dogs has grown significantly in the last decade. Selective breeding for flat-faced characteristics has led to an increased incidence of upper respiratory tract obstruction and subsequent respiratory distress. Whilst the length of the skull is reduced, the volume of soft tissues remains the same.

Affected dogs have to increase their respiratory rate and effort in order to compensate for the narrowed airway and subsequent obstruction. Increasing the inspiratory effort causes an increase in airway pressure which can cause hypertrophy of the tissues around the pharynx and cause weakening of the cartilages of the larynx, trachea and bronchi.

The most well-known components of BOAS include stenotic nares, overlong soft palate, eversions of the laryngeal saccules and hypoplastic trachea. It is now understood that there are many more components. The caudal ethmoturbinates grow caudally instead of cranially and obstruct the naso-pharynx. The tongue base is enlarged and causes further obstruction of the pharynx. The changes to the larynx are complex; there is often eversion of the laryngeal saccules (grade 1 collapse) but also weakening of the cartilage can lead to overlap of the cuniform process (grade 2) and eventually the dorsal corniculate process of the larynx (grade 3). Laryngeal collapse is secondary to repeated suction of the cartilages into the lumen due to high inspiratory pressures which causes chondromalacia (weakening).

Clinical signs

Although many brachycephalic dogs have some degree of stertor, in moderate to severely affected dogs the owners may describe they are snoring in the day as well as the night. Because of the increased airway obstruction when the pharyngeal muscles are relaxed, these dogs may have sleep apnoea and may choose to sleep with their neck stretched out or with an object in their mouth so they can breathe through their mouth when sleeping. When exercising, they often take a long time to recover, especially in hot weather. Severe cases may show signs of collapse and cyanosis. A high-pitched noise (stridor) can be heard in dogs with laryngeal collapse.

Reverse sneezing is often seen in brachycephalic dogs and is suspected to be related to irritation to the soft palate. It is a quite peculiar sound and can sound quite distressing to some owners and can last for a few minutes. It resolves spontaneously although anecdotally, can be resolved by rubbing the cranio-ventral neck area.

Dogs with BOAS are more prone to heat stroke and these dogs should not be exercised in hot weather and should have a cool area to rest at home.

Is surgery necessary?

The decision of which dogs to recommend surgery on is difficult as all brachycephalic dogs show some degree of clinical signs. There is a functional grading system developed by the University of Cambridge which is based on a 3 minute exercise tolerance test and aids the clinician in deciding whether a dog requires surgery.

| FUNCTIONAL GRADING SYSTEM | |

| Grade 0 | BOAS free, no surgery required |

| Grade 1 | Mild respiratory signs but not clinically affected, no surgery required but yearly monitoring advised |

| Grade 2 | Moderate clinical signs, requires intervention which involves weight loss +/- surgery |

| Grade 3 | Severe clinical signs, requires surgery |

Obesity is linked with BOAS as the fat is laid around the airways. For patients with mild to moderate signs, weight loss is recommended prior to surgery.

Diagnostic tests

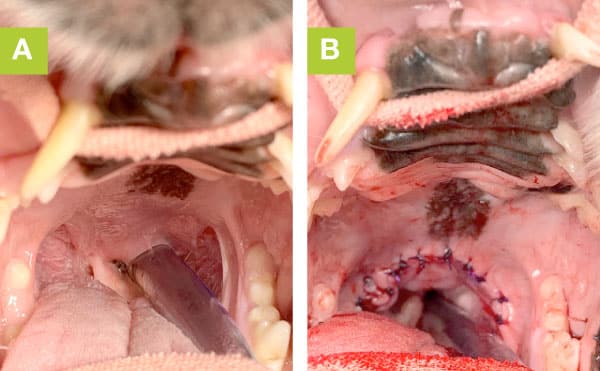

Dogs are anaesthetised for a thorough airway examination to be performed. The length of the palate is assessed; normally it should end just cranial to the epiglottis and should have a complementary shape. In dogs with BOAS the palate extends caudal to the oesophagus and, in severe cases even through the glottis. The tonsils are examined and it is noted whether or not they are everted. The larynx is thoroughly assessed to see whether the saccules are everted and whether the larynx is collapsed.

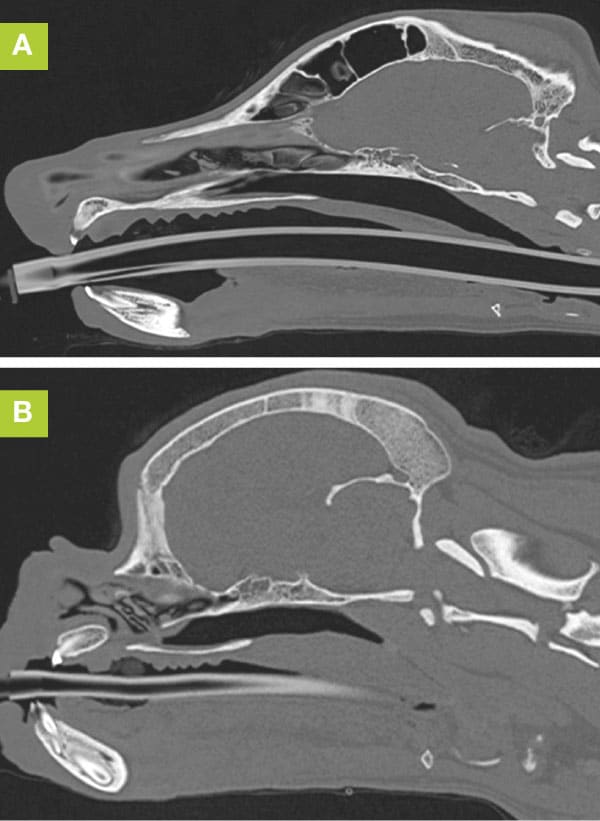

Thoracic imaging, either radiographs or a CT scan is used to identify any aspiration pneumonia and to assess for any other common abnormalities associated with BOAS such as hypoplastic trachea or a redundant oesophagus. CT of the head is useful as it can assess the thickness of the palate as well as the length and to assess for any aberrant nasal turbinates, macroglossia and septal deviation.

Surgery

The two main areas which are addressed initially are the nose and the palate. There are many different techniques that can be used to perform the rhinoplasty; vertical wedge, horizontal wedge, alar fold resection or Trader’s technique. The rhinoplasty can make a large difference to breathing as the nostril is the narrowest part of the respiratory tract.

Resection of the soft palate has become more aggressive in recent years. The palate is resected to the level of the rostral third of the tonsils by either a folding flap technique or a wide arch shaped cut and sew technique.

If the saccules occupy a large proportion of the lumen, we may elect to remove them. They are removed during extubation using fine surgical instruments. If there is grade 2 or 3 collapse and the dog did not improve following an initial surgery, we may elect to perform a partial laryngectomy. In addition, depending on the severity of the presenting signs, we may elect to remove the tonsils. A laser assisted turbinectomy may be necessary if there is a significant obstruction.

Regurgitation

Regurgitation is a common presenting sign of dogs with upper respiratory tract obstruction and occurs in 56% of dogs presenting with BOAS (Kaye 2018). The aetiology is complex but it is suspected that the increased airway pressures leads to an increase in gastro-oesophageal reflux and occasionally a sliding hiatal hernia. In addition, there can be oesophageal diverticulae (outpouching) which can contribute to regurgitation. In the study by Poncet et al (2016), through endoscopic evaluation of patients presenting with BOAS, there were endoscopic and even histologic changes in dogs even when there were no gastrointestinal clinical signs.

The use of omeprazole (1mg/kg PO BID), maropitant (1mg/kg PO SID) and in severe cases cisapride (0.2-1mg/kg PO TID) can help to reduce the severity and frequency of gastrointestinal signs. Even though the signs can be severe, there is often an improvement or resolution of the regurgitation post- airway surgery. In the study by Kaye et al (2018), all dogs improved following airway surgeries, French Bulldogs in particular. Even if there is a diagnosis of a sliding hiatal hernia, it is preferable to perform airway surgery initially and to give cisapride and omeprazole post-operatively.

Outcome

The main risks are recovery from the anaesthesia and aspiration pneumonia post-operatively. Dogs with grade 2 or 3 laryngeal collapse have more difficulties recovering from anaesthesia and rarely we need to place a tracheostomy tube for recovery. One study (Seneviratne 2020) looked at the outcome of dogs following staphylectomy and rhinoplasty and found that 70% of dogs improved post-operatively. For any dog that has not improved substantially after surgery, it is recommended to repeat the imaging and airway examination in case further surgery is required.

References

Kaye, B.M., Rutherford, L., Perridge, D.J., Ter Haar, G. Relationship between brachycephalic airway syndrome and gastrointestinal signs in three breeds of dog JSAP 2018

Poncet CM, Dupre GP, Freiche VG, Estrada MM, YA, Bouvy BM Prevalence of gastrointestinal tract lesions in 73 brachycephalic dogs with upper respiratory syndrome JSAP 2016

Seneviratne, M., Kaye, B.M., Ter Haar, G. Prognostic indicators of short-term outcome in dogs undergoing surgery for brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome Vet Rec 2020

Case Advice or Arranging a Referral

If you are a veterinary professional and would like to discuss a case with one of our team, or require pre-referral advice about a patient, please call 01883 741449. Alternatively, to refer a case, please use the online referral form

About The Discipline

Soft Tissue Surgery

Need case advice or have any questions?

If you have any questions or would like advice on a case please call our dedicated vet line on 01883 741449 and ask to speak to one of our Soft Tissue Surgery team.

Advice is freely available, even if the case cannot be referred.

Soft Tissue Surgery Team

Our Soft Tissue Surgery Team offer a caring, multi-disciplinary approach to all medical and surgical conditions.