These tumours make up a reasonable proportion of the cases we see at NDSR and of course this is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the cases in the wider population. There have recently been a number of developments in the diagnosis and management of these cancers.

There will be an emphasis on the most common bladder tumour which is a transitional cell carcinoma (TCC).

Diagnosis

The real key here is suspicion. Most patients with lower urinary tract neoplasia do NOT have physical examination findings which will specifically direct you to that conclusion. You have to suspect the disease and test for it appropriately. Equally, testing every dog which comes in with any lower urinary tract signs for cancer would be excessive.

Breed

Scottish Terriers are 18 times more likely than crossbreeds to be diagnosed with a transitional cell carcinoma. Shetland Sheepdogs, West Highland White Terriers and Beagles are also at increased risk, but not to the same magnitude.

Age

95% of dogs with a lower urinary tract carcinoma are older than six.

When to investigate more and when to treat symptomatically?

- If any ‘at risk’ breed over 6 years old has lower urinary tract signs, further investigation is warranted

- In dogs older than 6 which have signs, investigation is reasonable depending on the severity of signs and the owner’s wishes

- In dogs younger than 6, you are likely to be dealing with another problem and symptomatic treatment is likely to be appropriate.

- In any dog, persistent or recurrent signs should be investigated

Symptomatic Treatment

A simple urinary tract infection will often respond very well to NSAIDs and antibiotic treatment. Of course, it is better to do a culture-led antibiotic treatment, however there is a delay in getting the results and a cost with this too. Therefore, a short course of a broad-spectrum antibiotic, likely to reach high concentrations in the urine (such as amoxy/clav) is a reasonable approach.

Remember that improvement in response to antibiotics does not prove absence of neoplasia. Many dogs with lower urinary tract neoplasia have a concurrent urinary tract infection. 29% of males and 80% of females with TCC also have a UTI!

Further diagnostics

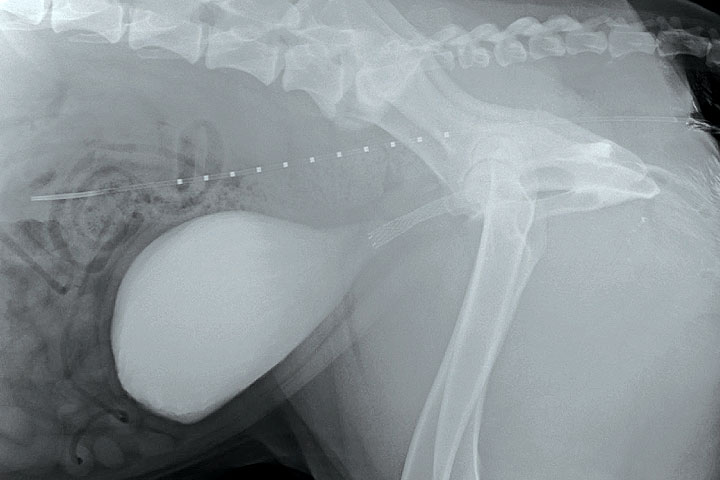

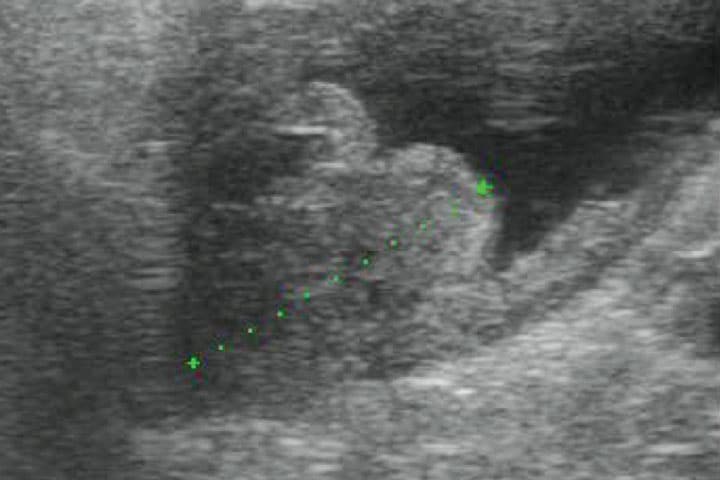

Ultrasound is probably the most useful test that we have to identify bladder masses. Normal bladder epithelium is smooth and if you see any rough surfaces or a mass projecting into the bladder, you should be concerned! The majority of TCCs are at the trigone. Significant masses can cause ureteric obstruction. This is indicated by hydronephrosis. The prostate and locoregional lymph nodes should also be examined.

The main differentials for a bladder mass will be a clot or a polyp. Clots can be distinguished using Doppler or by ballottement of the abdomen to see if the clot moves.

Biopsy is necessary to make a definitive diagnosis. Suction biopsy involves passing a catheter to the point of the mass and suctioning some cells back. It is also possible to biopsy using endoscopic grab forceps via the urethra with ultrasound to confirm its location. Be aware of the risk of tumour seeding by FNA. We believe this risk is elevated when the needle passes through the mass into the bladder lumen.

One point worth noting is that some dogs will have a urethral TCC, which can often only be diagnosed by cystoscopy. So, if you have compatible signs and signalment but no apparent mass, remember the urethral TCC.

Female

Male

96%

65%

Some dogs will have a urethral TCC, which can often only be diagnosed by cystoscopy. So, if you have compatible signs and signalment but no apparent mass, remember the urethral TCC.

Clinical Stage

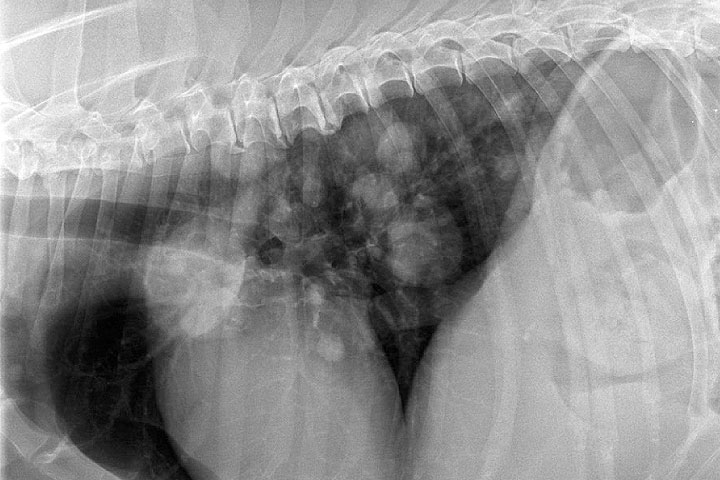

Transitional cell carcinomas are metastatic cancers. At the time of diagnosis, 30% will have metastasised to the local lymph nodes and 10% will have metastasised to the thorax.

Management

Supportive care

This is an absolutely crucial component of the care of dogs with this cancer. A lot of the dogs that we see with TCC have been treated symptomatically first with a temporary resolution of signs, showing how useful these treatments can be.

NSAIDs will alleviate discomfort associated with the tumour in 75% of cases. Some dogs will respond better to one than another so don’t be afraid to change after a suitable break if signs worsen. Although some good results are reported with piroxicam, this is not licensed and has a high chance of adverse effects (GI and renal). We recommend COX-2 selective agents for efficacy and safety reasons.

Other analgesia may be indicated. Tramadol, gabapentin and amantadine can all have a role. Antibiotics can be an important part of supportive care. Culture-directed treatment is advisable.

Stenting is a salvage procedure which can be used to relieve urinary obstruction in dogs which are blocked. It does not relieve straining and pollakiuria.

Urinary diversion by means of a cystostomy can remove the consequences of urethral obstruction.

Nappies can make an unbelievable difference to the quality of life of owners of patients with urinary incontinence secondary to lower urinary tract neoplasia.

Chemotherapy

This is the mainstay of our treatment. Although multiple drugs are reported to offer some efficacy, mitoxantrone is our preferred agent, given in conjunction with NSAIDs. Success is defined by improvement in clinical signs rather than measurable changes in tumour dimensions.

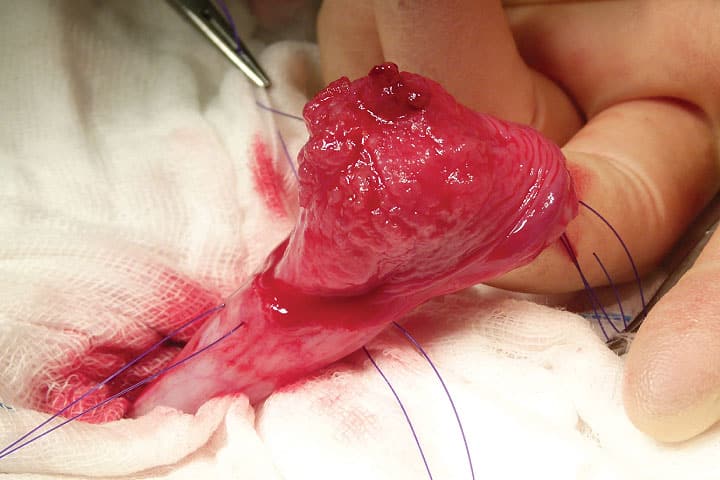

Surgery

The major and important benefit of surgery is an improvement in quality of life from physical removal of a painful lesion. Due to the location of most tumours, surgery is often contraindicated. Due to the transitional nature of the bladder epithelium, tumour recurrence always happens. For tumours situated away from the trigone, surgery is appropriate. However, outcomes following surgery alone are comparable to those with chemotherapy alone. Therefore, if it is a choice of one or the other, we will usually recommend chemotherapy.

Radiotherapy

Current radiotherapy systems we have in the UK do not appear to improve outcomes for dogs with TCCs. Newer systems not currently available in the UK do seem to be more useful, with 20 month survival times reported in small case series.

Key messages

- Further investigation for TCC is recommended in at-risk breeds over 6 years of age with signs of dysuria

- UTI is common. Do not exclude a TCC diagnosis on the basis of an improvement in response to antibiotics

- Treatments for all budgets: most TCC sufferers will enjoy significant clinical improvements in response to NSAID administration alone

- For the majority, best outcomes are achieved with the combination of COX-2 selective inhibitor and chemotherapy

Case Advice or Arranging a Referral

If you are a veterinary professional and would like to discuss a case with one of our team, or require pre-referral advice about a patient, please call 01883 741449. Alternatively, to refer a case, please use the online referral form

About The Discipline

Oncology

Need case advice or have any questions?

If you have any questions or would like advice on a case please call our dedicated vet line on 01883 741449 and ask to speak to one of our Oncology team.

Advice is freely available, even if the case cannot be referred.

Oncology Team

Our Oncology Team offer a caring, multi-disciplinary approach to all medical and surgical conditions.