The craniocervical junction is probably the most complex anatomical structure within the spine. It allows a wide range of motion of the head while protecting the spinal cord from compressive injury. The atlantoaxial spinal motion unit is a common site of craniocervical instability. Failure of the atlantoaxial supporting structures can result in dramatic neurological deficits such as sudden respiratory paralysis and cardiac arrest.

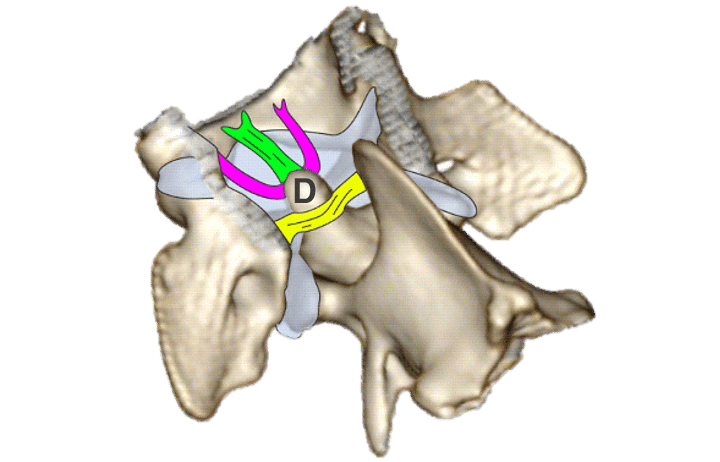

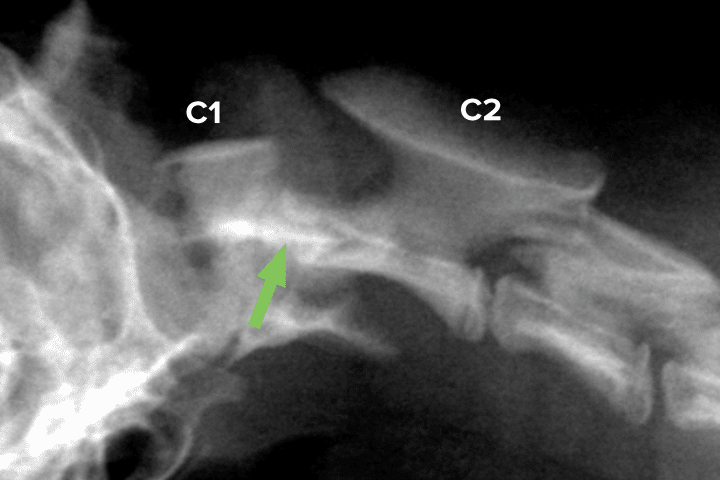

The stability of the atlantoaxial (AA) joint relies on the integrity of the dens of the axis and the AA supporting ligaments (See Figure 1). The dens together with the apical, transverse, and alar ligaments, form the atlanto-odontal system, which provides most of the ventral stability. A single dorsal atlantoaxial ligament, stretching from the C2 spinous process to the C1 dorsal arch, supports the AA joint dorsally. Paraspinal muscle tissue and articular capsule also contribute to AA stability, but failure of the ligamentous system is considered sufficient to cause AA instability.

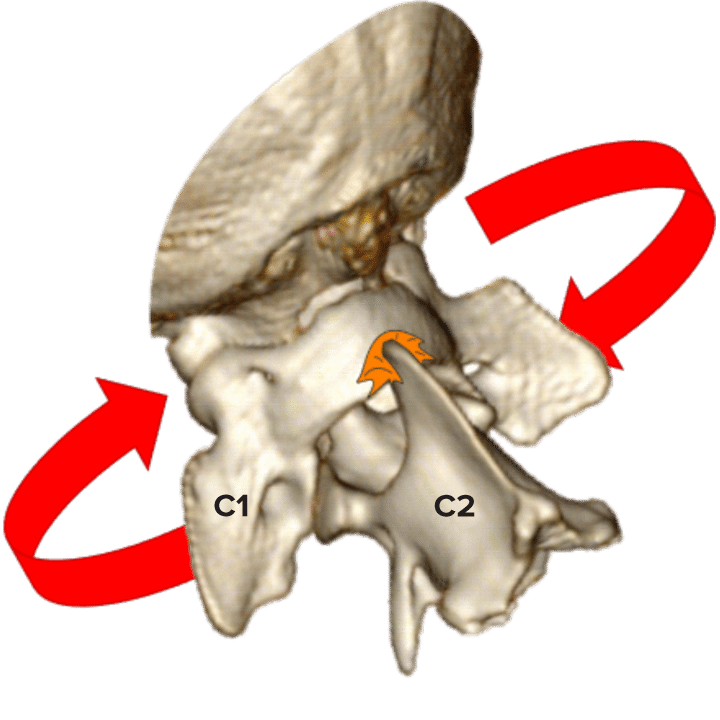

Both ventral and dorsal AA ligamentous distribution prevent excessive translation motions in any direction but allow a wide range of axial rotation necessary for head left to right rotations. In contrast, ventro-dorsal rotations of the head are mostly occurring at the level of the atlanto-occipital joint.

Failure of the atlantoaxial supporting structures

Spinal instability can be defined as an increased range of motion between two vertebrae resulting in discomfort and/or neurological deficits via compression or injury of the supported neural structures (spinal cord and nerve roots). Spinal instability can occur suddenly or gradually, depending on the nature of the underlying cause. At the level of the atlantoaxial joint, there are four common types of instability:

- Congenital ligamentous anomalies

- Congenital dens anomalies

- Complex craniocervical anomalies

- Traumatic craniocervical junction injuries

Congenital ligamentous anomalies

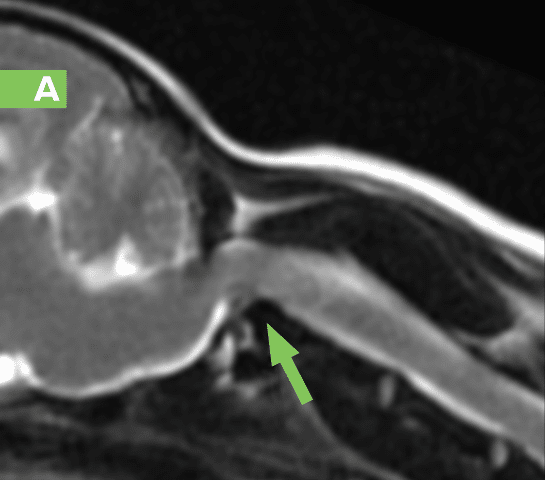

Occurs with dysplastic or aplastic AA ligaments. The ventral ligamentous support is generally considered to be the origin of the problem. Historically, post-mortem examination was necessary to evaluate ligamentous integrity. With the advent of MRI, it is now possible to detect ligamentous anomalies in vivo. This type of instability is expected to worsen progressively over time, although sudden clinical deterioration can also be observed. One theory explaining the slow clinical progression is that the dorsal ligament support is initially intact, preventing significant subluxation. However, because of insufficient ventral stability, the dorsal AA ligament is loaded with greater forces that it can sustain in long term. These excessive forces slowly stretch the dorsal AA ligament over time, causing a progressive increase in AA instability.

Congenital dens anomalies

Occurs with dysplastic or aplastic C2 dens causing failure of the ventral stabilising system. All four main ventral ligaments function by supporting the dens of C2. Anomalies of the dens result in similar instability as the ligamentous anomalies described above.

Complex craniocervical junction anomalies

Occurs with malformations in addition to the ones listed above. Small and Toy breeds (such as Chihuahua, Yorkshire terriers, Maltese or Miniature Dachshund) are most commonly affected by atlantoaxial instability. These same breeds are also predisposed to multiple other craniocervical malformations. Typical anomalies include C1 vertebral arches, atlanto-occipital overlapping, C2 dens dorsal angulation and caudal occipital malformations. The presence of concomitant malformation can sometimes aggravate the degree of instability and affect treatment options.

Craniocervical junction traumatic injuries

Occurs secondary to a traumatic injury resulting in sudden failure of the supporting atlantoaxial structure. These injuries can happen in any breed, although minor trauma can be sufficient to cause serious injuries in breeds having pre-existing congenital malformations. The C2 vertebral body is a frequent vertebral fracture site resulting in major instability.

Clinical signs

The clinical signs associated with AA instability are variable ranging from no detectable deficits to sudden cardio-respiratory arrest and many stages in between, such as intermittent pain, ataxia, tetraparesis and tetraplegia. Due to the location of the spinal cord injury, the associated ataxia can sometimes be challenging to characterise with both proprioceptive (erratic paw placement) and vestibular (imbalanced gait) ataxia described. On rare occasions, more severe vestibular signs have also been described, which have been attributed to the proximity of the brainstem vestibular nuclei.

Overall, neurological deficits suggestive of cervical myelopathy or cervical discomfort in a predisposed breed should raise suspicion for AA instability. Avoiding excessive cervical manipulation is essential in these patients because iatrogenic injury to the spinal cord can easily occur.

Investigations

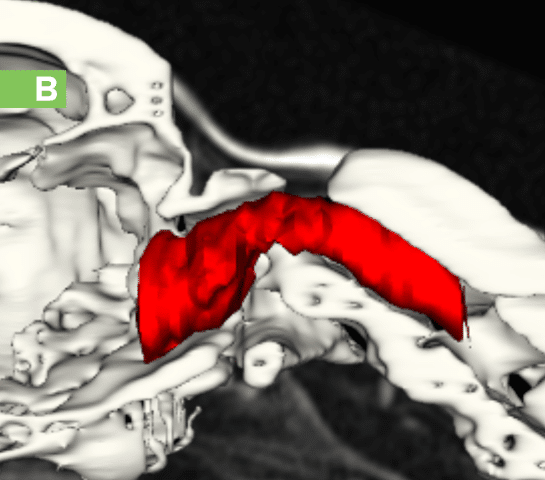

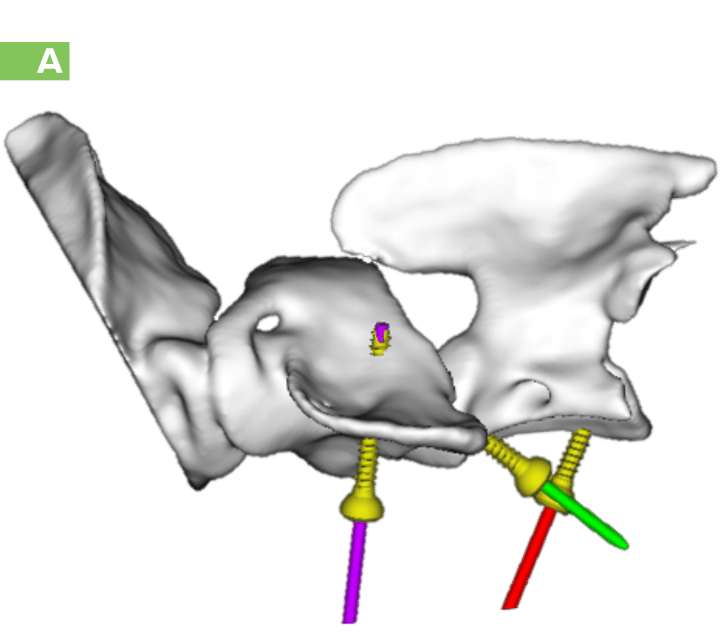

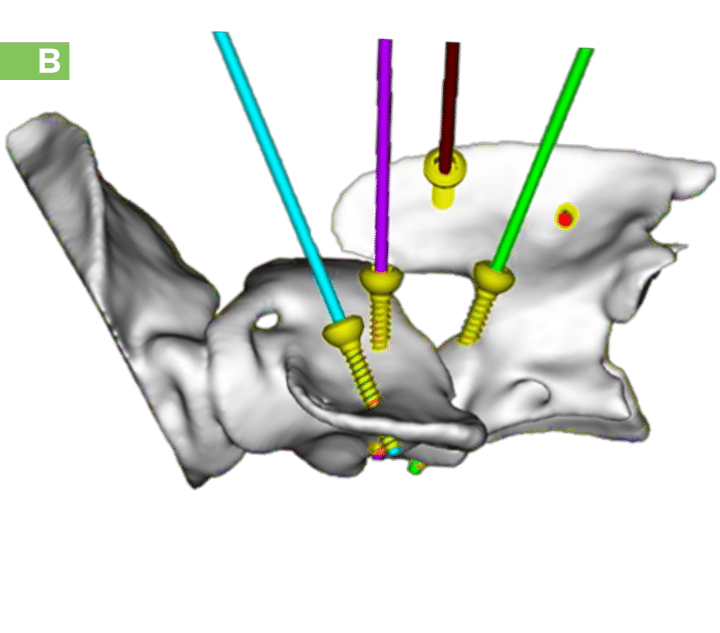

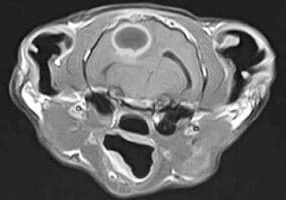

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered the gold standard investigation for spinal cord diseases. Computed tomography is another modality which is particularly valuable in assessing osseous malformations and generating 3D images that can be used for surgical planning (See Figure 2).

Treatment

Most publications refer to AA instability as a surgical condition. This is based on the principle that significant instability causing either pain or neurological deficits has the potential to worsen and cause acute clinical deterioration, which can be serious or even life-threatening. That being said, there are also reports of successful treatment with medical management, and for some patients, the instability may remain static for a very long time.

Our recommendation is to pursue surgical stabilisation if possible. Many surgical techniques have been described in the literature. The most common techniques involve multiple pins or screws embedded in bone cement placed ventrally to the AA joint (See Figure 4). However, there is growing evidence that a similar method used dorsally may be just as successful and could reduce some of the complications observed with ventral techniques. The main limitation of pursuing surgical intervention is the relatively high reported mortality rate in the literature (in the range of 0-10% in recent publications).

In situations where surgical intervention is not possible, temporary immobilisation of the cervical spine using a bandage and/or casting materials is often recommended while treating discomfort pharmacologically and providing any rehabilitation necessary.

AA instability key points

- AA instability occurs predominantly in Toy breeds, even though any dog can be affected.

- Plain radiographs can be sufficient to diagnose AA instability.

- MRI and CT scans are valuable tests used to investigate the integrity of the craniocervical junction and plan stabilisation surgeries.

- Neck manipulation should not be applied in patients where AA instability is suspected or confirmed to avoid iatrogenic injuries.

- Surgery is advised for any case of confirmed AA instability while carefully considering the associated risks.

Case Advice or Arranging a Referral

If you are a veterinary professional and would like to discuss a case with one of our team, or require pre-referral advice about a patient, please call 01883 741449. Alternatively, to refer a case, please use the online referral form

About The Discipline

Neurology

Need case advice or have any questions?

If you have any questions or would like advice on a case please call our dedicated vet line on 01883 741449 and ask to speak to one of our Neurology team.

Advice is freely available, even if the case cannot be referred.

Neurology Team

Our Neurology Team offer a caring, multi-disciplinary approach to all medical and surgical conditions.