Both cats and dogs suffer from seizures, however the diagnostic and treatment approach for cats differ greatly from their canine companions, and, at times, it can seem frustrating and challenging.

We can find many causes for Feline Epilepsy, from metabolic problems, toxins, or genetics. Therefore, a complete diagnostic approach is necessary to determine a diagnosis. A full history, physical and neurological examination are always crucial.

- Structural epilepsy (intracranial cause)

Is more likely in cats that are over 7 years of age, who show vocalisation during the ictal phase or have abnormal neurological examination.

Different types of Epilepsy in cats:

Feline Idiopathic Epilepsy (or Epilepsy of Unknown Origin):

Feline Idiopathic Epilepsy (of unknown origin) is diagnosed in 22% of cats suffering seizures. Overall, cats can develop idiopathic epilepsy at any age (range 0.4 to 14 years), but median age is around 4.5 years old.

The diagnosis is made by exclusion, ruling out of other causes for seizures. MRI and CSF, along other diagnostic tests, are typically normal.

Considerations for Feline Idiopathic Epilepsy include:

- Possible post-ictal urinary retention, especially after cluster seizures

- Higher remission rate than dogs: up to 44% of cats with idiopathic epilepsy will achieve seizure freedom

- Better survival and prognosis than dogs with idiopathic epilepsy

- Careful selection of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs): not all can be used in cats (potassium bromide can have dangerous side effects such as bronchoalveolitis, so therefore it is not recommended).

Treatment for Feline Idiopathic Epilepsy:

First-Line Treatment is phenobarbital, starting at 2-3 mg/kg every 12 hours. It can reduce seizure activity with efficacy up to 93%. Phenobarbital has liver metabolism, but in cats, auto-enzyme induction is negligible and therefore drug concentrations are not expected to decrease overtime. For this reason, monitoring of serum levels is less important than in dogs. The time for phenobarbital to reach steady state is 10 to 12 days in cats. Common side effects such as sedation, polyuria, polydipsia, and excessive hunger are expected. Pseudolymphoma has been reported as a side effect of phenobarbital use in a cat.

Levetiracetam is a safe and effective AED for cats, used at 10 to 30mg/kg every 8 hours. Levetiracetam has few side effects and has minimal hepatic toxicity, but the short elimination half-life prevents as good control as monotherapy. It is best used as an add on treatment for idiopathic epilepsy or for other types of epilepsy such as FARS.

Diazepam (Oral) used at 2 to 5mg/Kg TID can be used in cats as functional tolerance does not seem to develop as it does in dogs, but it is not first choice treatment. A rare side effect of acute hepatic necrosis can occur and must be taken into account when using this drug in feline patients.

Imepitoin (Pexion) is safe to use in cats, but more studies are needed to recommend it as monotherapy for epilepsy.

Feline Audiogenic Reflex Seizures (FARS)

Feline audiogenic reflex seizures is an important type of epilepsy in cats and is triggered by various high-pitched noises, usually causing a strong startle reflex called myoclonic seizures.

Noises that trigger FARS:

- Crinkling tin foil

- A metal spoon clanging in a ceramic feeding bowl

- Chinking or tapping of glass

- Crinkling of paper or plastic bags

- Tapping on a computer keyboard or clicking of a mouse

- Clinking of coins or keys

- Hammering of a nail

- Clicking of an owner’s tongue

FARS occurs more frequently in:

- Older cats over 10 years of age, usually 15 years old

- Birman cats

- Cats with hearing impairment (50%)

- Triggered by particular noises, different for each cat

Cats suffering FARS usually present with myoclonic seizures, but generalised tonic-clonic seizures and absence seizures can also occur as part of this syndrome. Myoclonic seizures only last for a fraction of a second, and many cats will appear to remain conscious throughout. The seizure is characterised by brief involuntary muscle jerks or spasms, and this was the type of seizure seen in almost 95% of the FARS cats studied.

Treatment for Feline Audiogenic Reflex Seizures:

Levetiracetam is the treatment of choice for FARS: according to one study, Levetiracetam reduced the number of myoclonic seizures in cats with FARS by at least 50%, while also having fewer side effects than phenobarbital. In cats with generalised tonic-clonic seizures as well as myoclonic seizures, phenobarbital may be used along levetiracetam.

Hippocampal Necrosis

Hippocampal and piriform lobe lesions can be found on brain MRI and histopathology of some cats with a particular clinical presentation of seizures.

Clinical signs include:

- Generalised seizures

- Behavioural changes

- Aggression

- Salivation

Clinical signs also reported in association with hippocampal necrosis include:

- Complex partial seizures with motor arrest (motionless starring)

- Automatism

- Orofacial involvement

- salivation, facial twitching, lip smacking, chewing and licking

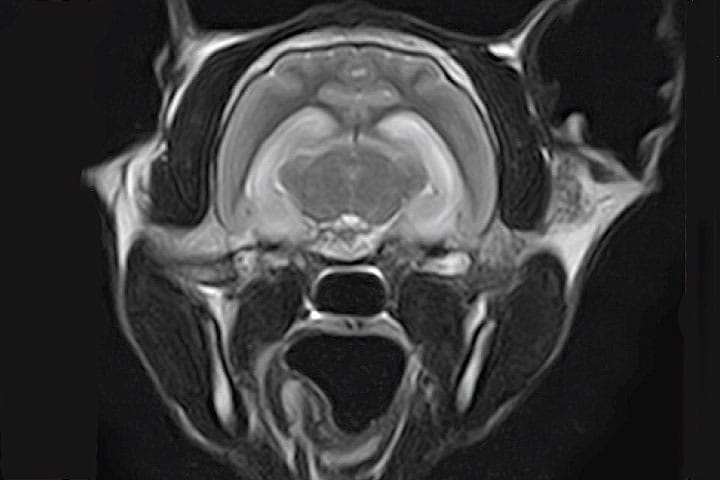

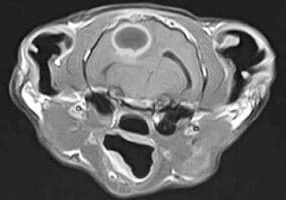

MR imaging abnormalities are restricted to the hippocampus and piriform lobe. The lesions are T2-hyperintense, T1-hypointense, and with various degrees of contrast enhancement.

Histopathologic findings in euthanised cats found severe, diffuse, bilateral symmetric necrosis, and degeneration of neurons in the hippocampus and piriform lobe, along with pronounced astrogliosis and mild lymphocytic inflammation.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis in some cases reveals elevated protein content and nucleated cell count with mixed pleocytosis. However, these findings are difficult to interpret as mixed pleocytosis in the CSF following seizures has been previously reported in dogs.

Hippocampal necrosis has different aetiologies, and sometimes a clear cause remains unknown. Seizure activity itself can cause histopathological changes in the hippocampus, making it difficult sometimes to know if the seizures were the cause or the consequence of the changes observed in the hippocampus.

Image: T2 weighted image showing hippocampal hyperintensity consistent with hippocampal necrosis or limbic encephalitis

Feline Temporal Lobe Epilepsy:

Feline Orofacial Seizures (FEPSO) Linked to VGKC-Complex-Ab Limbic Encephalitis

This is a form of epilepsy related to hippocampal necrosis in cats. This presentation is also referred to as FEPSO. The features have some similarity to those described in humans with limbic encephalitis and voltage-gated potassium channel (VGKC) complex antibodies. Accumulating evidence suggests that these epileptic seizures originate from the temporal lobe (TL) in cats.

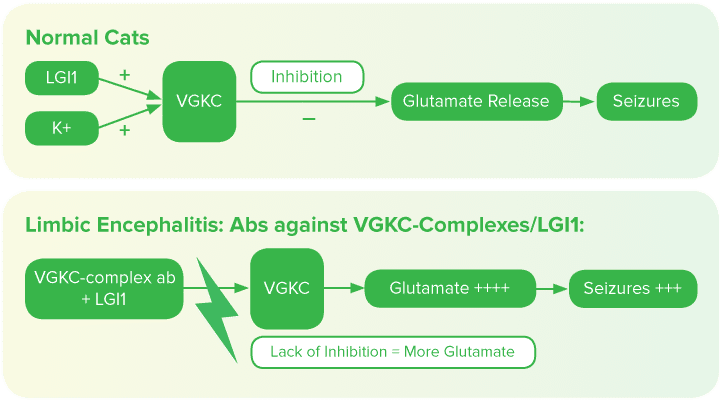

Pre-synaptic voltage-gated potassium channels (VGKC) in the brain have an inhibitory function over glutamate release. As glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter, VGKC activity reduces seizure activity. These channels work along a family of proteins, especially leucine-rich glioma inactivated 1 (LGI1), that allow VGKC to be active.

VGKC-complex antibodies against LGI1 have been found in a cohort of cats (5/14) with seizures and MRI or histopathological signs of hippocampal necrosis, suggesting that an autoimmune process causes inactivation of LGI1 and VGKC, causing more glutamate release and therefore decreasing the seizure threshold. Follow-up sera were available for 5 cats in remission and all antibody concentrations were within the reference range. This study suggests that an autoimmune limbic encephalitis exists in cats and that VGKC-complex/LGI1 antibodies may play a role in this disorder, as they are thought to in humans.

Treatment is based on supportive treatment, immunosuppressive drugs such as corticosteroids along with phenobarbital and other AEDs (levetiracetam and diazepam). Resistance to treatment is common, although some reports describe good control when treatment was started early and aggressively, with some cats even achieving remission.

Hippocampal Necrosis and Temporal Lobe Epilepsy Linked to Brain Tumours

Contrary to previous reports of FHN in which no underlying cause could be identified, a case report of a cat with seizures consistent with FEPSO and signs of hippocampal necrosis on MRI, identified that the seizure focus arose from a neoplastic lesion within the right pyriform lobe. This unique case report represents the so-called ‘dual pathology’ of temporal lobe epilepsy in humans, in which an extrahippocampal lesion within the temporal lobe results in hippocampal sclerosis.

- Conclusion: feline epilepsy can be complicated to diagnose

- Metabolic, toxic, infectious and structural causes should be ruled out first

- Intracranial pathologies are more likely if cats are old, vocalise during the ictal phase or have abnormal neurological examination

- Idiopathic epilepsy can occur at any age in cats, and it carries a better prognosis for remission than in dogs

- Potassium Bromide must not be used in cats due to severe adverse effects

- Phenobarbital serum levels do not need to be monitored as frequently as in dogs

- There are recognised forms of feline epilepsy, such as FEPSO (orofacial seizures) linked to hippocampal necrosis, or FARS (feline audiogenic reflex seizures) with specific treatments and prognosis.

References:

Barnes Heller H. Feline Epilepsy. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2018;48(1):31-43.

Boothe DM, George KL, Couch P. Disposition and clinical use of bromide in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002;221:1131–1135.

Charalambous M, Pakozdy A, et al. Systematic review of antiepileptic drugs’ safety and effectiveness in feline epilepsy. BMC Vet Res. 2018 Mar 2;14(1):64.

Kitz S, Thalhammer JG, Glantschnigg U, et al. Feline Temporal Lobe Epilepsy: Review of the Experimental Literature. J Vet Intern Med. 2017 May;31(3):633-640.

Pakozdy A, Sarchahi AA, Leschnik M, et al. Treatment and long-term follow-up of cats with suspected primary epilepsy. J Feline Med Surg 2013;15:267–273.

Pakozdy A, Halasz P, Klang A, et al. Suspected limbic encephalitis and seizure in cats associated with voltage-gated potassium channel (vgkc) complex antibody. J Vet Intern Med 2013;27:212–214.

Pakozdy A, Gruber A, Kneissl S, et al. Complex partial cluster seizures in cats with orofacial involvement. J Feline Med Surg 2011;13:687–693.

Schmied O, Scharf G, Hilbe M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of feline hippocampal necrosis. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2008;49:343–349.

Vanhaesebrouck AE, Posch B, et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy in a cat with a pyriform lobe oligodendroglioma and hippocampal necrosis. J Feline Med Surg. 2012 Dec;14(12):932-7.

Case Advice or Arranging a Referral

If you are a veterinary professional and would like to discuss a case with one of our team, or require pre-referral advice about a patient, please call 01883 741449. Alternatively, to refer a case, please use the online referral form

About The Discipline

Neurology

Need case advice or have any questions?

If you have any questions or would like advice on a case please call our dedicated vet line on 01883 741449 and ask to speak to one of our Neurology team.

Advice is freely available, even if the case cannot be referred.

Neurology Team

Our Neurology Team offer a caring, multi-disciplinary approach to all medical and surgical conditions.