Non-infectious meningoencephalomyelitis are common neurological conditions in dogs which may lead to inflammation of the brain, surrounding meninges and spinal cord. The aim of this article is to provide you with an overview on these conditions, focusing on meningoencephalitis of unknown origin.

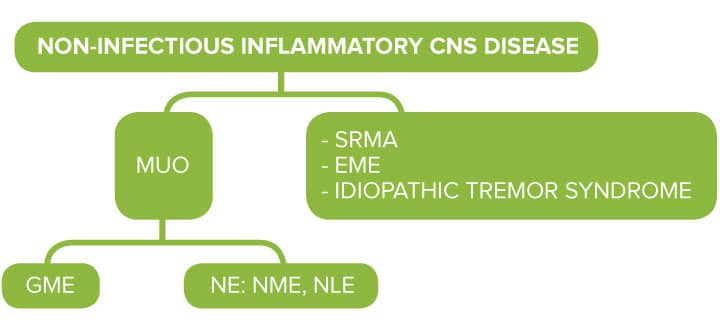

The classification of central nervous system (CNS) non-infectious inflammatory disease often appears confusing as several different names and acronyms exist to refer to these conditions. This mirrors the presence of different subtypes of non-infectious CNS diseases and depends on the achievement of a definitive histological or of a presumptive clinical diagnosis.

Meningoencephalitis of unknown origin (MUO)

The following subtypes of CNS non-infectious inflammatory diseases have been reported:

- Granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis (GME)

- Necrotising encephalitis (NE), which includes necrotising leukoencephalitis (NLE) and necrotising meningoencephalitis (NME)

- Steroid-responsive meningitis arteritis (SRMA)

- Eosinophilic meningoencephalitis (EME)

- Idiopathic tremor syndrome (cerebellitis)

Classification of CNS non-infectious inflammatory diseases

What is MUO?

Meningoencephalitis of unknown origin (MUO) is the most common cause of meningoencephalitis in dogs. It is a clinical diagnosis, therefore the term ‘MUO’ is used to refer to all those cases in which the final diagnosis is not made based on histopathology and includes GME, NLE and NME.

GME may present with 3 different forms: multifocal, focal, optic. May represent up to 25% of canine disease.

Eosinophilic meningoencephalitis, SRMA and idiopathic tremor syndrome are not generally referred to as ‘MUO’ due to the different clinical presentation, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) abnormalities and histopathology findings.

MUO

Acronym for ‘meningoencephalitis of unknown origin’ which is used when GME or NE are suspected, in the absence of a hystopathological diagnosis

GME, NE

Acronyms for ‘granulomatous meningoencehalomyelitis’ and ‘necrotising encephalitis’, based on a histopathological diagnosis

In order to achieve a definitive diagnosis, CNS biopsy should be performed; this may however be cost prohibitive and may result in neurological deterioration. For this reason, the diagnosis of MUO is generally based on neurological examination, cross-sectional imaging findings, and CSF abnormalities, and obtained after ruling out infectious diseases.

The suggested guidelines for the anti-mortem diagnosis of MUO include the following criteria of inclusion:

- Dogs older than 6 months

- MRI changes refecting multiple, single or diffuse intra axial T-2 weighted hyperintensities

- Pleocytosis on CSF analysis with > 50% mononuclear cells

- Exclusion of infectious diseases (eg: Neospora caninum, Taxoplasma gondii)

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of MUO is not well understood, however genetic, immunologic, and environmental (e.g. infection, tissue injury) factors are suspected triggers for the underlying autoimmune inflammatory response.

Signalment, history, clinical presentation

Young to middle age, medium to small toy breeds are the most commonly affected, however dogs of all breeds and of all ages can be diagnosed with MUO and approximately 25% are large breed dogs. The onset of the clinical signs is often acute and quickly progressive, and commonly reflects multifocal CNS disease.

Systemic involvement is not normally expected in these cases, therefore the physical examination and laboratory findings (haematology, biochemistry, electrolytes) will be normal in most of the affected dogs. Differently from SRMA, MUO rarely causes pyrexia.

Neurological presentation

Commonly observed neurological deficits are altered mental status, vestibulocerebellar signs (e.g. head tilt, circling, loss of balance), seizures, visual deficits, tetraparesis and ataxia. These vary depending on the anatomical distribution of the lesions which will often be multifocal or diffuse and asymmetrical.

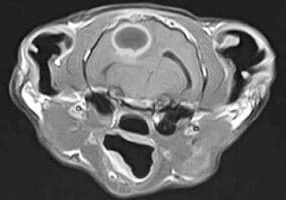

In approximately 8% of the cases the neurological signs reflect spinal cord involvement only, and particularly in these cases cervical hyperaesthesia can be a common finding.

GME may manifest in three different syndromes:

- focal form

- multifocal or disseminated form

- ocular form.

The multifocal form generally leads to acute and rapidly progressive signs; the focal form is insidious and with slower progression; the optic form leads to acute blindness.

Main differential diagnosis

The main differential diagnosis to consider for dogs presenting with acute progressive multifocal CNS signs include:

- metabolic disease (e.g. hepatic encephalopathy, toxin)

- infectious meningoencephalitis (e.g Toxoplasmosis, Neosporosis, bacterial meningoencephalitis)

- intracranial neoplasia

Diagnostic work-up

Common diagnostic testing typically includes: complete blood count (CBC), chemistry panel, bile acids stimulation test to rule out systemic disease, advanced crosssectional imaging via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) collection and analysis. Infectious causes for meningoencephalomyelitis are tested depending on the specific geographic area. Although the prevalence of protozoal infection causing meningoencephalitis is low in the UK (0.25% for Toxoplasma gondii; 2.25% for Neospora caninum), Toxoplasmosis and Neosporosis are generally ruled out through serum antibody titres and/or PCR for antigen identification within the CSF. Microbial culture of CSF may be considered in case of suspected bacterial infection. Canine distemper virus is uncommon in vaccinated dogs, whereas Rickettsial and fungal disease are very rare in the UK.

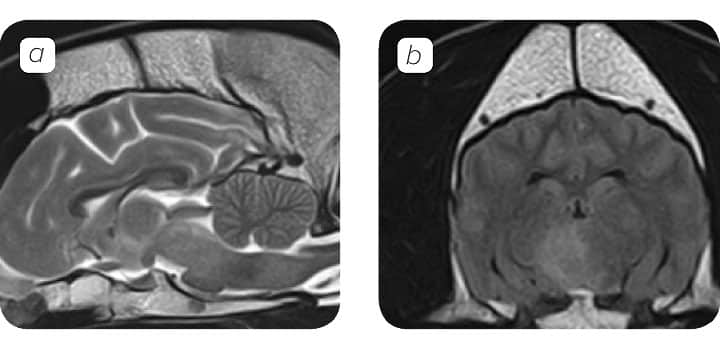

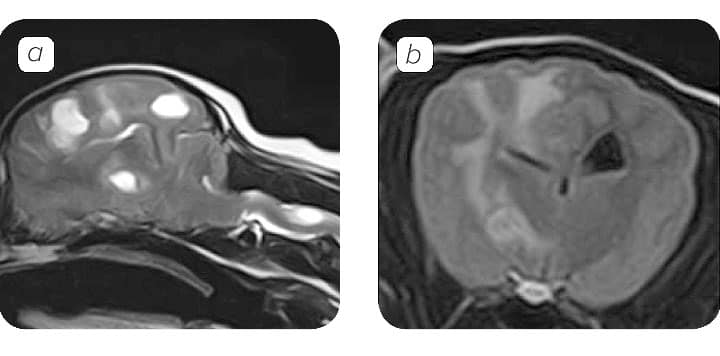

MRI Findings

MRI is the imaging modality of choice for CNS inflammatory disease.

The MRI appearance of meningoencephalitis is nonspecific, however in many cases the lesions observed are:

- Multifocal

- Irregular, ill-defined

- Hyperintense in T2- weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images.

A normal brain MRI unfortunately does not rule out CNS inflammatory disease, as in approximately 25% of the cases is normal. Although, ante-mortem definitive diagnosis of GME, NME or NLE is not possible, characteristic imaging features may be suggestive of one or the other. MRI findings of focal GME may be indistinguishable from neoplasia.

CSF analysis

Although in 12.5-22% of the dogs with MUO the CSF analysis can result normal, in most of the cases reveals mononuclear (lymphocytes, monocytes) or mixed pleocytosis and elevated protein concentration.

It is however important to keep in mind that cytology rarely provides definitive differentiation among immune-mediated, infectious, and neoplastic disorders but when this is combined with history, signalment and cross-sectional imaging of the CNS, may guide the clinician in the identification of the most likely diagnosis.

MRI Findings

Treatment

Immunosuppressive therapy is treatment of choice for MUO. Several therapeutic protocols have been described; glucocorticoids such as prednisolone represent the mainstay of treatment and are often combined with other immunosuppressive drugs (e.g. cytosine arabinoside (CA) and/or cyclosporine). These are generally administered at tapering doses over several months and the duration of treatment will vary depending on each individual clinical response.

Although repeating CSF analysis and MRI would provide greater sensitivity for prediction of relapse, the response to treatment is generally monitored by clinical evaluation and by documenting the resolution of neurologic deficits, in order to overcome the costs and risks linked to further investigations.

Prognosis

MUO is fatal if not treated promptly and with the appropriate treatment and its prognosis is guarded.

The median long-term survival times reported, range from 28 to 1834 days, with approximately 25-33% of the cases dying or being euthanised within 1 week after diagnosis, despite the initiation of treatment. Dogs whose response to treatment remains favourable after 1 month, seem to have better chances of a good longer-term outcome.

Prognostic indicators in dogs treated for MUO are not well characterised, however an association with a shorter survival time has been reported in dogs presenting with:

- Multifocal/disseminated lesions

- Brainstem lesions

- Seizures

- Foramen magnum herniation

- Loss of cerebral sulci

Key Messages

- MUO is the most common form of meningioencephalitis

- MUO rarely causes pyrexia

- Normal imaging and CSF does not rule out a diagnosis of MUO

- Treatment of MUO is immunosuppressive therapy but prognosis is guarded with a 25% one week mortality

Case Advice or Arranging a Referral

If you are a veterinary professional and would like to discuss a case with one of our team, or require pre-referral advice about a patient, please call 01883 741449. Alternatively, to refer a case, please use the online referral form

About The Discipline

Neurology

Need case advice or have any questions?

If you have any questions or would like advice on a case please call our dedicated vet line on 01883 741449 and ask to speak to one of our Neurology team.

Advice is freely available, even if the case cannot be referred.

Neurology Team

Our Neurology Team offer a caring, multi-disciplinary approach to all medical and surgical conditions.