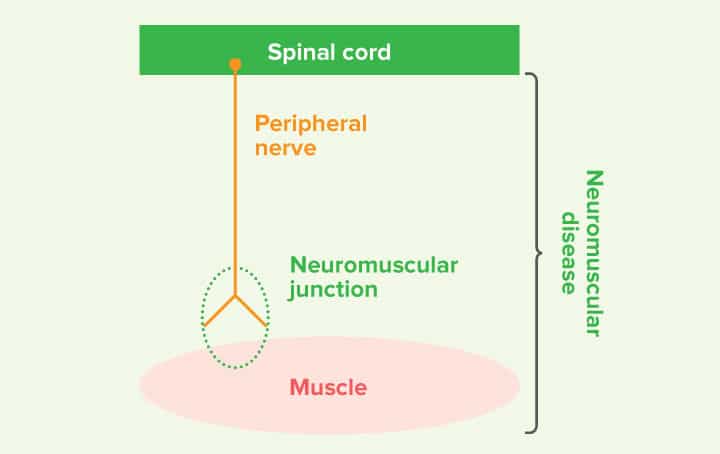

Neuromuscular diseases affect the peripheral nervous system and either affect the peripheral nerves (neuropathies), neuromuscular junction (junctionopathies) or the muscle itself (myopathies). In this focus on piece we hope to explain the most common causes of acute onset flaccid paralysis and an overview of the current best practice for diagnosis and treatment.

Dogs with acute onset neuromuscular disease will commonly start with signs of weakness and a short strided gait in the pelvic limbs which will then affect the thoracic limbs and over 24-72 hours they progress to being unable to walk with a flaccid tetraparesis or tetraplegia (absence of voluntary movement).

The most noticeable features on examination will be:

- Motor dysfunction with inability to walk and support weight in any limb.

- Reduced muscle tone in all limbs with very reduced to absent spinal reflexes (e.g. withdrawal reflexes)

- Some will have weak muscles of the head and neck.

- Some diseases may also affect cranial nerves causing dysphonia (change in the bark), difficulty swallowing, prehending or chewing food.

The most common causes of acute neuromuscular disease in the UK are:

- Polyradiculoneuritis

- Botulism

- Fulminant myasthenia gravis

In animals that have travelled to the USA and Australia, tick paralysis is also another major differential.

Less common causes include:

- Toxins (algae, snake & spider venom)

- Endocrinopathies (hypoadrenocorticism, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism)

- Paraneoplastic syndromes (eg. insulinoma)

- Infectious disease (Toxoplasma & Neospora)

- Inflammatory immune-mediated myopathies or neuropathies.

Idiopathic polyradiculoneuritis

This is an inflammatory condition affecting multiple peripheral nerves (polyneuropathy) in dogs and is considered to be the equivalent of Guillain-Barre syndrome in man. Affected dogs usually present with:

- Rapidly developing non-ambulatory tetraparesis or tetraplegia within 10 days of the initial onset of clinical signs.

- Usually retain the ability to wag their tail and maintain bladder function despite paralysis.

- Proprioception is relatively well preserved when supported as long as they have enough residual motor function to perform the movement.

Predisposed breeds include the West Highland White Terrier and Jack Russell Terrier and there is a seasonality to the disease with more dogs being affected in autumn and winter.

The cause of polyradiculoneuritis is currently unknown but an immune-mediated process is suspected. It has historically been associated with a recent raccoon bite, although an identical syndrome is seen in countries without a raccoon population. A recent study has shown that raw chicken meat consumption is a risk factor in dogs, potentially mediated by Campylobacter species (also postulated in man). A recent study found no significant association between polyradiculoneuritis and recent vaccination.

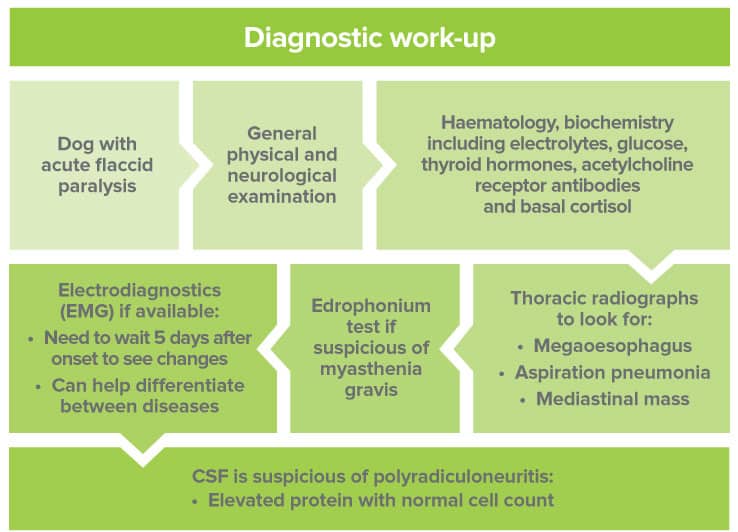

Definitive diagnosis is made from histopathological examination of nerve root biopsies. This is quite invasive and thus rarely performed, so a presumptive diagnosis is currently made by excluding other diseases and supportive clinical criteria, electrodiagnostics and lumbar cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis.

Typically, the CSF will have an albuminocytological dissociation meaning that there is an elevated protein level (>45mg/dL) with a normal cell count (

On electrodiagnostics we will often see classic changes including evidence of abnormal spontaneous activity in the muscles due to denervation.

There is no specific treatment and, despite being an immune-mediated disease, steroids do not appear to be effective and instead increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia and speed of muscle atrophy. There is one study on the use of intravenous immunoglobulins and this showed only a trend towards a significantly faster recovery time.

For the main part, treatment in dogs is supportive with nursing care to include turning frequently, thick bedding, monitoring for aspiration pneumonia and physiotherapy to avoid contractures and maintain muscle mass.

Provided the disease does not result in respiratory failure or euthanasia, dogs usually recover, although full recovery can take up to 6 months. We usually see return to walking within the first 6 weeks.

Myasthenia Gravis

Myasthenia gravis is a junctionopathy and can either be congenital (due to deficiency or abnormality of acetylcholine receptors) or acquired due to immune-mediated attack of the acetylcholine receptors.

This disease commonly occurs in young dogs

- 36% of dogs have a focal form with megaoesophagus only and the rest have a generalised form.

- A small percentage have an acute fulminating form where there is a rapidly progressive non-ambulatory tetraparesis, megaoesophagus and respiratory disease.

- A concurrent mediastinal mass is rarely found in dogs (3-4% of cases) but is found in around 50% of cats.

Diagnosis:

- Chest radiographs to look for megaoesophagus +/- mediastinal mass

- Acetylcholine receptor antibodies are very specific and have a 90% sensitivity.

- Electrodiagnostics typically show minimal spontaneous activity (which helps distinguish from neuropathies or myopathies) and depreciation in repetitive nerve stimulation.

- Edrophonium (tensilon) response test is a rapid way of confirming a clinical suspicion (0.1-0.2mg/kg edrophonium IV). This is a short acting AChE inhibitor which causes a transient improvement in signs lasting seconds to a few minutes. We often give atropine to reduce the risk of a cholinergic crisis (salivation, urination, lacrimation, defaecation).

Treatment

- Anticholinesterase therapy with oral pyridostigmine at 0.5-3mg/kg PO BID

- If regurgitating too much initially then neostigmine 0.4mg/kg IM.

- Immunosuppression with steroids is controversial and risks include aspiration pneumonia and worsening muscle weakness.

- Thymectomy is recommended in dogs with a thymoma or those responding poorly to medical therapy.

Botulism

Botulism is caused by bacterial neurotoxins produced by Clostridium botulinum. Dogs are most commonly affected by ingestion of preformed neurotoxin in raw meat. The toxin reaches the pre-synaptic nerve terminals and interferes with the release of acetylcholine filled vesicles (the signalling molecule at the NMJ). This causes a neuromuscular blockade and neurological signs develop within hours up to 6 days after ingestion.

Clinical findings

- Flaccid tetraparesis with severely decreased to absent spinal reflexes but normal mental status.

- Concurrent cranial nerve dysfunction very common often with reduced jaw tone, reduced gag reflex with excessive salivation, decreased palpebral reflexes and dysphonia.

- Autonomic signs including alterations in heart rate (tachycardia or bradycardia), mydriasis with sluggish PLR, constipation, urinary retention and neurogenic keratoconjunctivitis sicca.

Definitive diagnosis is based on detection of neurotoxin in blood, faeces or vomitus although this is rarely done due to the large quantities needed. The most reliable method of detecting toxin is the mouse inoculation test; however, this test is rarely used due to the expense and use of live animals. Demonstration of a 4-fold increase in botulinum neurotoxin antibody titre over 2 weeks is reliable but the results come when recovery is well underway or complete.

Treatment consists of supportive care only and all affected dogs recover in 14 to 24 days unless secondary complications develop such as infections or respiratory failure.

Key messages

- Neuromuscular disease is characterised by muscle weakness, reduced tone, reduced to absent spinal reflexes and in some cases cranial nerve involvement.

- The 3 most common acute neuromuscular conditions causing flaccid paralysis in dogs are idiopathic polyneuritis, botulism and fulminant myasthenia gravis.

- This can be a neurological emergency-in severe cases they may need intensive care treatment such as ventilation due to respiratory muscle weakness.

- Thoracic radiographs are advised to check for megaoesophagus, cranial mediastinal mass and aspiration pneumonia which may alter prognosis and treatment.

- Presence of autonomic signs may make botulism the most likely differential.

- Presence of megaoesophagus is uncommon in polyradiculoneuritis so consider botulism or myasthenia.

- Electrodiagnostics are helpful in trying to differentiate between diseases.

Case Advice or Arranging a Referral

If you are a veterinary professional and would like to discuss a case with one of our team, or require pre-referral advice about a patient, please call 01883 741449. Alternatively, to refer a case, please use the online referral form

About The Discipline

Neurology

Need case advice or have any questions?

If you have any questions or would like advice on a case please call our dedicated vet line on 01883 741449 and ask to speak to one of our Neurology team.

Advice is freely available, even if the case cannot be referred.

Neurology Team

Our Neurology Team offer a caring, multi-disciplinary approach to all medical and surgical conditions.