Idiopathic Epilepsy is a condition that affects more than 0.6% of dogs in the UK1 and it can have a significant detrimental effect on the quality of life of the dog and the family.

Many owners suffer feelings of fear, stress and uncertainty, resulting in lifestyle changes far greater than previously estimated2.

Here we will address scenarios for:

- Uncontrolled dogs under treatment with Phenobarbital

- Uncontrolled dogs under treatment with Imepitoin

- Dogs already on two AEDs (Refractory Epilepsy)

- Dogs already on three AEDs

Diagnosis of genetic epilepsy is based on the following:

– Autonomic signs (salivation, urination)

– Short-lived (unless status epilepticus)

– Post-ictal period and/or pre-ictal period

– Full recovery in between episodes,

If the first 5 criteria are met, the chances of intracranial disease is very low (2.2%) MRI is especially recommended for dogs that do not meet these criteria3,4.

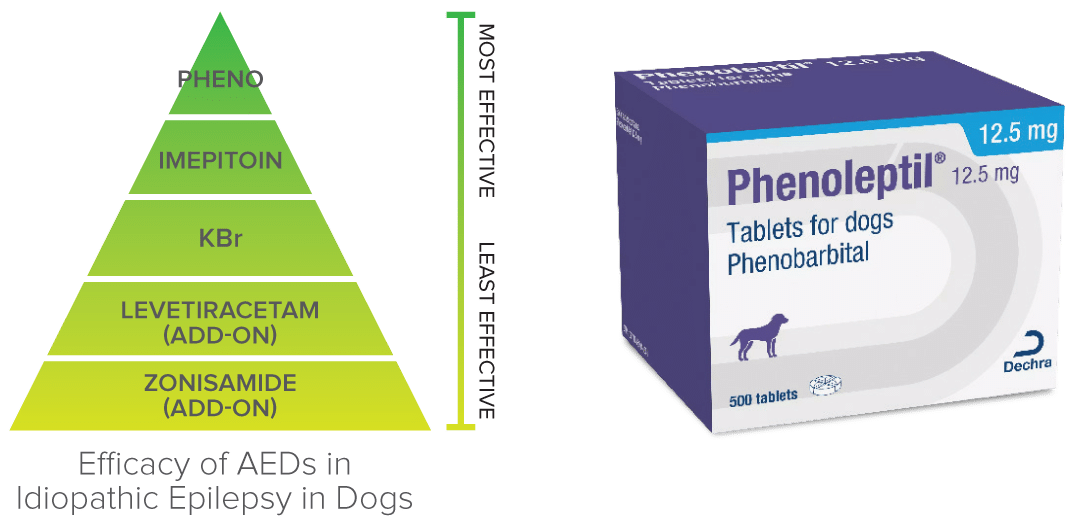

With the many anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) on the market and the addition of new treatment modalities, it is understandable that confusion may arise when dealing with an epileptic dog that is not well-controlled by their current medication5.

The first-line AEDs are Imepitoin and Phenobarbital. Following initiation of treatment with one of these medications, you should expect that the frequency and severity of seizures will reduce by at least 50%. But what happens when the seizure frequency does not decrease by 50%, or if it increases again after some time?

30-35 µg/ml (or mg/L)5

- If levels are now closer to the suggested range: monitor seizure frequency for a period of time depending on seizure frequency (usually 3 times the longest interictal period for the dog).

- If levels are still low, increase the dose and retest as above.

- Potassium bromide may be more effective but will take 2 to 3 months to reach adequate levels. Serum levels should be checked after 3 months. Side effects can include sedation, polyphagia and polydipsia, gastrointestinal problems, occasionally pancreatitis, skin problems or paresis. A loading dose is possible (600mg/kg divided in more than 8 doses, over 48 hours) but will cause excessive sedation. Levels can be checked 1 month after loading dose.

‘Desirable’ KBr serum levels:

2000 mg/L5 - Levetiracetam has a high safety profile and low risk of side effects. It is effective in a shorter period of time and it is not necessary to monitor serum levels 7.

one

two

- If already on levetiracetam, add potassium bromide.

- If on potassium bromide, add levetiracetam.

- Measure phenobarbital serum levels at peak (4 hours after phenobarbital oral dose) and trough (0 hours, before phenobarbital dose).

- If there is too much disparity between these values (less than 20h half-life)*, consider phenobarbital dosing every 8 hours instead of every 12 hours, maintaining the same total daily dose (or slightly increased if safe to do so).

*Phenobarbital elimination half-life (T1/2) = 0.693/Kelim, where Kelim=[Ln (PB peak)–Ln (PB trough)]/time interval1

Key Points

- Conclusion: Idiopathic epilepsy can be difficult to manage but applying a stepwise approach enables you to achieve the best possible control with the fewest treatments and side effects

- Suspect idiopathic epilepsy if dog aged 6m-6y at onset of seizures and normal neurological examination and bloods

- Always remember to run a bile-acid stimulation test alongside initial bloods to rule out extra-cranial causes of seizures

- Always maximise serum levels of one drug before considering addition of another

- Imepitoin is not licensed for focal or cluster seizures. phenobarbital should be used in these cases

- If phenobarbital is at adequate serum levels and seizure control is not adequate consider adding levetiracetam or potassium bromide

References

- Stabile et al. Phenobarbital administration every eight hours: improvement of seizure management in idiopathic epileptic dogs with decreased phenobarbital elimination half-life. Vet Rec. 2017;180(7):178.

- Pergande et al., ‘We have a ticking time bomb’: a qualitative exploration of the impact of canine epilepsy on dog owners living in England. BMC Vet Res. 2020;16(1):443

- Smith et al. Findings on low-field cranial MR images in epileptic dogs that lack interictal neurological deficits. Vet J. 2008; 176(3):320-5

- De Risio L, Bhatti S, Munana K, et al. International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force consensus proposal: diagnostic approach to epilepsy in dogs. BMC Vet Res 2015;11:148

- Bhatti S, De Risio L, Muñana KR, et al. International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force consensus proposal: medical treatment of canine epilepsy in Europe. BMC Vet Res 2015;11:176

- Muñana KR. Management of refractory epilepsy. Top Compan Anim Med 2013;28(2):67-71

- Muñana KR, Thomas WB, Inzana KD, et al. Evaluation of levetiracetam as adjunctive treatment for refractory canine epilepsy: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Vet Intern Med 2012;26(2):341-348

- Dewey CW, Guiliano R, Boothe DM, et al. Zonisamide therapy for refractory idiopathic epilepsy in dogs. JAAHA 2004;40(4):285-291

- Law TH, Davies ES, Pan Y, et al. A randomised trial of a medium-chain TAG diet as treatment for dogs with idiopathic epilepsy. Br J Nutr 2015;114(9):1438-1447

- McGrath S, Bartner LR, Rao S, et al. Randomized blinded controlled clinical trial to assess the effect of oral cannabidiol administration in addition to conventional antiepileptic treatment on seizure frequency in dogs with intractable idiopathic epilepsy. JAVMA 2019;254(11):1301

Case Advice or Arranging a Referral

If you are a veterinary professional and would like to discuss a case with one of our team, or require pre-referral advice about a patient, please call 01883 741449. Alternatively, to refer a case, please use the online referral form

About The Discipline

Neurology

Need case advice or have any questions?

If you have any questions or would like advice on a case please call our dedicated vet line on 01883 741449 and ask to speak to one of our Neurology team.

Advice is freely available, even if the case cannot be referred.

Neurology Team

Our Neurology Team offer a caring, multi-disciplinary approach to all medical and surgical conditions.