“Feline eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis is probably best described as a disease that cannot be cured, only controlled. This is helpful to bear in mind, particularly when counselling owners”

In part one of this series on feline eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis (FEK) – a chronic, progressive infiltrative disease of the cornea and conjunctiva in cats – we looked at how to recognise the condition. In this second part, we will be discussing how to diagnose and treat it.

Although immunosuppressive treatment is paramount to the successful treatment of FEK, there are multiple factors that veterinary practitioners must consider before determining the final treatment strategy. But what are these factors? How do they impact treatment options? And what challenges might we expect to encounter during the treatment journey? This article will reveal all.

Diagnostic tests for feline eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis

Corneal cytology: when in doubt, “smear” it out!

Whenever raised lesions are found on the cornea and/or conjunctiva, the most useful diagnostic test is cytological assessment. Concerns regarding corneal fragility sometimes deter many practitioners; however, fears of iatrogenic globe perforation are unfounded for raised lesions (as opposed to deep lesions). This is because the cornea is a very tough collagenous structure that tolerates diagnostic surface scraping well.

Sampling technique

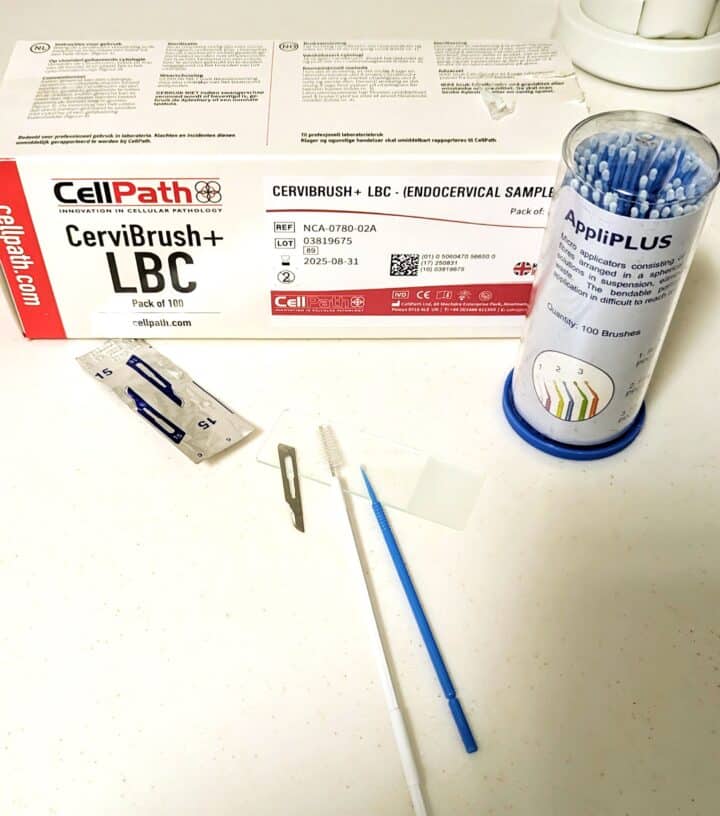

After the application of a drop of a topical anaesthetic agent (eg proxymetacaine 0.5 percent), cells may be gathered from the corneal/conjunctival plaques using select equipment. This might be a microbrush (dental applicator sponge), cytobrush (commonly used for endocervical sampling in women), kimura spatula or the blunt end of a sterile scalpel blade (Labelle and Labelle, 2023) (Figures 1A and 1B). Fine needle aspiration using a 25G x ½ inch needle without suction has also been described (Rodrigues et al., 2021).

It may be helpful to rest the hand holding the instrument against the animal as a stabilising point. Use a brisk scraping movement with a gentle pressure sufficient to abrade cells to collect the sample, then spread onto a clean, dry microscope slide and stain with Diff-Quik.

Cotton-tipped applicators and swab sticks (Figure 1C) are less ideal for obtaining corneal cytology samples, as while they may collect the sample well, they are less effective at releasing cells onto the glass slide (Labelle and Labelle, 2023).

Typical cytological findings

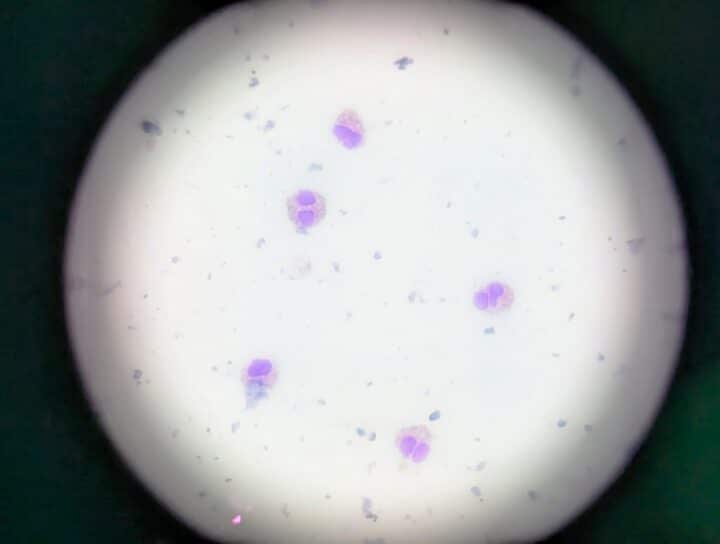

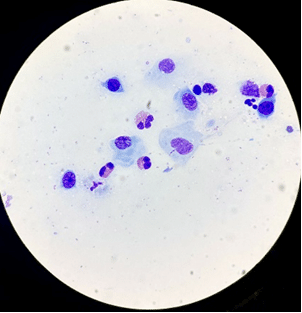

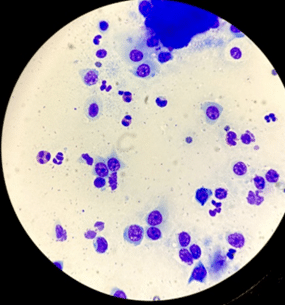

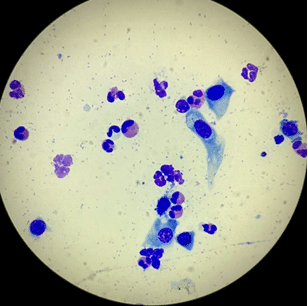

A slide of an FEK sample is usually dominated by eosinophils (Figure 2), with variable numbers of mast cells, neutrophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells, as well as corneal epithelial cells that may be dysplastic (Figures 3 and 4) (Lucyshyn et al., 2021; Maggs, 2018; Spiess et al., 2009).

Eosinophils are not typically found on healthy feline corneas, and their presence has been assumed to be pathognomonic of FEK. To veterinary ophthalmologists, seeing even one eosinophil in a feline corneal cytology sample is sufficient to make the diagnosis.

What if the corneal changes are highly suspicious, but I can’t find any eosinophils in the sample?

Look for eosinophilic granules amid any nuclear debris that could be suggestive of ruptured eosinophils (Figure 5). If the first sample is equivocal, sometimes taking a second “deeper” sample can help.

One study that involved concurrent cytological and histological examination of lesions in nine cats with FEK (10 samples) enabled better characterisation of the distribution of cells in the corneal plaques (Prasse and Winston, 1996).

The authors found that:

- Samples from superficial layers of the cornea were composed of epithelial cells, cellular debris that included eosinophilic granules, mast cells and lower numbers of intact eosinophils

- Eosinophils and lymphoid cells were predominantly visible in deeper scrapings

- Mast cells were less frequent in samples collected from the white exudative material on the corneal surface. Samples collected from the raised pink regions of the affected cornea in the same cat contained a mixed inflammatory cell population of mast cells, eosinophils, neutrophils and lymphocytes

Therefore, failure to find eosinophils in a sample may simply reflect the tissue depth at which the scraping was performed (ie too superficial).

Feline herpesvirus-1 testing

Testing for feline herpesvirus (FHV-1) can be fraught with logistical and interpretive challenges and ambiguity. Virus isolation, immunofluorescence assays and PCR are available, but each has shortcomings (Table 1).

| Virus isolation | Immunofluorescent antibody assay | Polymerase chain reaction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detects | Virus | Viral protein | Viral DNA |

| Viable virus needed? | Yes | No | No |

| Do vital stains (eg fluorescein) affect the result? | Yes | Yes | No (possibly) |

| Collection and transport technique | Complex |

Simple | Simple |

| Differentiates vaccine virus from wild-type virus? | No | No | No |

When interpreting FHV-1 test results, practitioners must consider that ocular FHV-1 shedding can be intermittent, so a negative result may not necessarily mean the virus is not present. There are also times when the PCR assay can be falsely negative despite its sensitivity. Further, the detection of FHV-1 can be incidental to, or even induced by, ocular disease in cats; this means its presence does not automatically mean that it has caused the primary disease process (Glaze et al., 2021; Maggs, 2005).

A positive result may certainly help justify antiviral therapy. However, irrespective of whether the virus is found and whether it is there as cause, effect or coincidence in relation to the primary disease process (FEK), the clinician must still decide whether specific antiviral treatment is warranted in each individual case. It is clinical acumen rather than any laboratory test that can answer this question. Client funds might be better used toward treatment rather than antiviral testing.

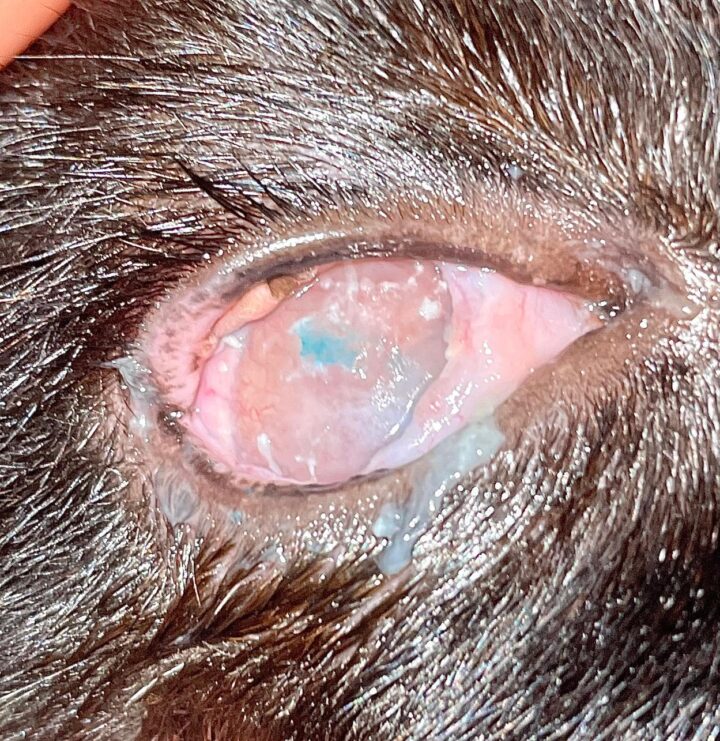

Fluorescein testing

As discussed in part one of this series, concurrent corneal ulceration is relatively common with FEK. If an ulcer is detected, topical antibiosis is recommended to prevent bacteria from gaining a foothold. It is important to flush off excess stain to avoid pooling in surface irregularities, which is very common with FEK plaques. Identification of a branching pattern of ulceration (ie dendritic lesions) can be a clue of active herpetic disease (Nasisse, 1990).

Schirmer tear testing

Schirmer tear testing (STT) has historically been considered quite unreliable in cats due to the assertion that low values may result from stress-induced increased sympathetic tone, causing a temporary reduction in tearing during testing (Lim et al., 2009). Sebbag et al. (2020) debunked this way of thinking, although poor test-retest repeatability may still be problematic (Sebbag et al., 2015).

Although keratoconjunctivitis sicca is considered rare in cats compared to dogs, it is recognised as a metaherpetic disease, whereby low tear production can be the result of conjunctival goblet cell depletion secondary to primary herpetic disease or reduced corneal sensitivity due to herpetic injury of the trigeminal nerve. An STT of less than 9mm/min in conjunction with clinical signs of keratoconjunctivitis is likely significant (Sebbag et al., 2015). Assessing the tear film in FEK cats may, therefore, be important and could potentially provide further clues about possible FHV-1 involvement.

Treatment strategies for feline eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis

Due to our understanding of FEK as an immune-mediated condition, immune suppression and/or modulation is the cornerstone of treatment. Topical, oral and parenteral options have been described (Table 2). The main aim of medical management is to achieve clinical remission and then reach the lowest effective dose of medications. If FHV-1 involvement is suspected, an antiviral and elimination of known stressors are also crucial components of therapy.

| Route | Drug | Dose | Frequency | Efficacy | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topical | Dexamethasone 0.1% solution | One drop | q6 to 24h (depending on the level of inflammation) | No specific data available | No specific data available |

| Prednisolone acetate 1% suspension | One drop | q6 to 24h | No specific data available | No specific data available | |

|

Ciclosporin A 0.2% to 1.5% ointment/suspension

(Allgoewer et al., 2001; Déan and Meunier, 2013; Spiess et al., 2009) |

One drop | q8 to 12h | 1.5 percent ciclosporin: 89 percent improved, 11.4 percent non-responsive | 1.5 percent ciclosporin: 22.6 percent recurrence | |

| Tacrolimus 0.02% to 0.5% suspension/solution

(Romaneck and Sebbag, 2021) |

One drop | q8 to 12h | No specific data available | No specific data available | |

| Megestrol acetate 0.5% solution

(Stiles and Coster, 2016) |

One drop | q8 to 12h (taper to q48 to 72h over a few months) | 88 percent improved, 12 percent non-responsive | 33 percent recurrence. Most cats required a treatment frequency of once every other day to once weekly to maintain remission of disease | |

| Oral | Megestrol acetate (tablets) | Start with 2.5 to 5mg PO q24h | 5mg q24h for seven days, then 2.5mg q24h for seven days, then 2.5mg EOD for seven doses

(Bedford and Cotchin, 1983) |

No specific data available | No specific data available |

| 2.5mg q24h for two weeks, then 2.5mg q72h for two weeks, then 2.5mg once weekly as a maintenance dose

(Stiles and Coster, 2016) |

No specific data available | No specific data available | |||

| 2.5 to 5mg q24 to 72h as an induction dose, then 2.5 to 5mg q7 to 14 days

(Labelle and Labelle, 2023) |

No specific data available | No specific data available | |||

| Parenteral | Triamcinolone acetonide (solution for injection)

(Lucyshyn et al., 2020; Romaneck and Sebbag, 2021) |

0.1 to 0.2mg/kg SQ | Can repeat 7 to 15 days after first injection | No specific data available | No specific data available |

| 1 to 4mg subconjunctival injection | Can repeat four to six weeks after first injection | No specific data available | No specific data available |

Topical corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids are generally regarded as the first-line treatment for FEK. A common initial choice is topical 0.1 percent dexamethasone sodium phosphate (Maxidex or Maxitrol, which also contains polymyxin B and neomycin) at one drop q6, 8 or 12h depending on clinical severity. Therapeutic response is evidenced by the resolution of the corneal plaques and gradual recession of corneal vascularisation.

Some clinicians favour ointment formulations of these drugs as they stick to the ocular surface for longer periods and, thus, may be slightly longer acting. Topical prednisolone acetate 1 percent is equally effective, but this is generally favoured for its good intraocular penetration, which is not necessary in FEK cases.

When substantial clinical improvement is seen or clinical remission is achieved, treatment is usually tapered by one daily drop every one to two weeks to the lowest effective maintenance dose. (This may be anything from one drop q48h to one drop once or twice weekly.)

Long-term administration of topical corticosteroids is undesirable, however. Therefore, most clinicians will try to wean patients off completely after instituting an alternative topical immunomodulator, if possible.

The clinical dilemma

While topical corticosteroids are not only (typically) effective in addressing FEK but readily available and inexpensive, the presence of corneal ulceration and potential involvement of FHV-1 in some cases can complicate management. Corticosteroids are a double-edged sword:

- They may induce FHV-1 reactivation from latency or exacerbate recrudescent herpetic disease (Nasisse, 1990), leading to recurrent ulceration and other signs of herpetic disease

- They may delay healing as well as predispose to bacterial superinfection, corneal protease potentiation and keratomalacia (Lucyshyn et al., 2020) when used in the face of pre-existing corneal ulceration. Corneal sequestration and abscessation following topical corticosteroids has also been reported in one case (Déan and Meunier, 2013)

Additionally, long-term topical corticosteroid use may induce corneal lipidosis and has been associated with subcapsular cataract formation and (reversible) ocular hypertension in cats(Zhan et al., 1992).

What is the solution?

If active corneal ulceration is noted concurrently with FEK, prophylactic topical antibiotic therapy may be initiated first, and immunosuppressant treatment started only once re-epithelialisation has occurred. Ideally, antibiotic choice would be guided by cytological inspection of the ulcerated area to ascertain bacteria type (ie cocci, rods, etc).

Alternatively, a different type or route of immunomodulatory therapy may be chosen (see below) in conjunction with a topical antibiotic. As Maxitrol has some antibiotic effect by virtue of its containing polymyxin B and neomycin, some clinicians do not shy away from prescribing this in FEK cases with only simple, superficial corneal ulcers. But close monitoring for clinical deterioration (eg frequent follow-up) is essential in these cases.

Given the potential for feline herpesvirus to be a causative or exacerbating agent, some ophthalmologists consider anti-herpesviral therapy to be one of the pillars of their FEK treatment strategy. Certainly, if there is suspicion of FHV-1 involvement – such as disease chronicity, dendritic ulcers suggestive of active viral replication, current or historical upper respiratory tract signs or stressors noted from history-taking – it would be prudent to begin treatment with an antiviral for one or two weeks before commencing or alongside immunomodulatory treatment.

In the UK, the most common antiviral treatment options for FHV-1 are oral famciclovir at 90mg/kg BID or topical ganciclovir (Virgan gel). However, the first is expensive and does not taste appealing to cats, and the second must be applied at least four to six times daily to be effective since all topical antiviral agents are only virostatic and thus more likely to induce viral resistance if under-dosed.

Other topical immunomodulators

The lacrimostimulant calcineurin inhibitors ciclosporin A and tacrolimus are perhaps better known for their usefulness in treating keratoconjunctivitis sicca in dogs. However, they also act as immunomodulators by inhibiting T-lymphocyte activation.

Ciclosporin

As FEK often requires prolonged treatment, most ophthalmologists try to find a steroid-sparing substitute such as topical ciclosporin(eg Optimmune 0.2 percent ointment) for long-term control, reserving topical corticosteroid for future flare-ups. Ciclosporin can also be used first-line as a sole agent and may be helpful in cases with ulceration because it does not have cytotoxic effects and does not affect the re-epithelialisation of the cornea (Liang et al., 2012).

In the literature, 1.5 percent ciclosporin (compounded in corn oil) two or three times daily was reported to have a treatment success rate of 89 percent and led to improvement in 31 of 35 cats (Spiess et al., 2009). Commercially available 0.2 percent ciclosporin does work and would probably be more sensible in terms of availability and following the cascade (Allgoewer et al., 2001).

The main thing of note regarding ciclosporin is the potential for side effects such as marginal blepharitis, which was reported in 1.5 percent of cats in one study of 35 cases (Spiess et al., 2009), or other signs of intolerance (ocular irritation, chemosis, conjunctival hyperaemia) in some cats.

Combination therapy has also been reported, with ciclosporin at 0.2 percent found to be useful in 9 out of 45 cats where corticosteroid treatment alone was ineffective (Déan and Meunier, 2013). In fact, many clinicians often start a topical steroid and topical ciclosporin concurrently with the rationale that while topical ciclosporin is safer for long-term use, it takes longer to reach therapeutic levels. It is, thus, forward-thinking to get it on board in the background while the topical steroid gets to work quickly to control the disease.

Tacrolimus

Tacrolimus has been used as part of a combination therapy, alongside subcutaneous triamcinolone, in one case report (Romaneck and Sebbag, 2021). It was given four times daily and slowly tapered off over three months. This was a specially compounded preparation of aqueous-based, 0.5 percent tacrolimus and was cited to be chosen based on the reasoning:

- Tacrolimus is more potent than ciclosporin for reducing corneal neovascularisation in severe keratitis

- In the authors’ experience, they believed it to be better tolerated in cats than oil-based compounded ciclosporin

In the UK, tacrolimus is available off-label as a specially compounded 0.02 percent ophthalmic solution (BOVA), as well as 0.03 percent and 0.1 percent human skin ointment (Protopic).

Topical NSAIDs

In general, the literature suggests that topical NSAIDs alone show a lack of efficacy in resolving FEK (Ahn et al., 2010; Labelle and Labelle, 2023). It would seem, therefore, that the mechanism of action of corticosteroids in this disease may be associated more with immunomodulatory effects than anti-inflammatory ones. However, the anti-inflammatory effects of topical NSAIDs are useful in active keratitis, particularly for calming down corneal vascularisation. If a clinician was being cautious and wanted to avoid corticosteroid for fear of exacerbating FHV-1 infection or precipitating melting ulceration, a topical NSAID (eg ketorolac) might just be what they would reach for in conjunction with ciclosporin 0.2 percent and an antiviral.

Corticosteroid therapy via other routes

Oral steroids

Oral steroids(eg prednisolone acetate at 1 to 2mg/kg/day) have been used in cases with a great extent of corneal involvement, but for a short period (under three weeks) (Déan and Meunier, 2013). However, it is not the first choice due to the high dosage needed for immunosuppression and the well-known systemic signs, including polydipsia and polyuria, and possible iatrogenic diabetic mellitus. The risk of causing recrudescence of herpetic disease remains (Gaskell and Povey, 1973).

Parenteral corticosteroids

Using subcutaneous administration of triamcinolone acetonide (0.1 to 0.2mg/kg) in the management of FEK has more recently been reported and appears to be well tolerated and efficacious (Lucyshyn et al., 2020; Romaneck and Sebbag, 2021).

Triamcinolone acetonide is an intermediate-acting glucocorticoid which is available as an injectable suspension (Kenalog) and is licensed for the treatment of inflammation and related disorders in dogs, cats and horses. It is considered approximately seven times as potent as methylprednisolone. In the BSAVA formulary, the recommended dose for cats is 0.1 to 0.2mg/kg intramuscularly or intralesionally and it is reported to be effective for three to four weeks.

What does the literature say?

In the literature, subconjunctival injection of doses up to 4mg injected at one site has been reported (Brightman et al., 1979; Morgan et al., 1996), as well as subcutaneous injection, with repeat injection appropriate if clinical remission is not seen within 7 to 15 days (Boehringer Ingelheim, 2014; Lucyshyn et al., 2020).

A case report by Romaneck and Sebbag (2021) featured a cat with bilateral severe EK that was non-responsive to 0.1 percent dexamethasone largely due to poor patient and owner compliance. Subcutaneous triamcinolone acetonide 0.2mg/kg was administered twice, 11 days apart, and was reported to not only help control clinical signs fairly rapidly but also improve therapeutic compliance to the point that adjunct topical therapy was possible by day five.

Lucyshyn et al. (2020) described a series of nine cats that were subcutaneously administered triamcinolone as the initial/primary immunomodulatory treatment for FEK. Antivirals were started one to two weeks prior to treatment and continued in light of the concern that cats treated with systemic corticosteroids are at risk for herpetic reactivation (Gaskell and Povey, 1973; Hickman et al., 1994). No signs of herpetic recrudescence or other systemic side effects (eg diabetes mellitus) occurred. Aditionally, triamcinolone administration appeared not to hinder corneal wound healing, as all cats in the study population with corneal ulceration healed within a median period of 14 days.

While subcutaneous triamcinolone for FEK needs to be more thoroughly assessed in future prospective case-controlled studies involving a larger population of cats, the above preliminary data suggests that it offers effective immunosuppression and may be useful in ulcerated eyes where topical corticosteroid is contraindicated. It also obviates the need for daily administration of medication which is a boon in fractious cats or those not amenable to topical treatment.

Alternative treatment options

Oral megestrol acetate

Megestrol acetate (MgA; Ovarid) was the first medical treatment found to be consistently effective against FEK at a time when the recommended treatment was keratectomy (Bedford and Cotchin, 1983; Brightman et al., 1979). This treatment is thought to be useful in cats with recurrent disease recalcitrant to topical therapy(Morgan et al., 1996).

MgA is a potent progestogen with anti-oestrogen and glucocorticoid-like activity. Although it remains highly effective, the side effects associated with its use, and it no longer being available in the UK, mean that it has largely fallen out of favour. (The side effects include uncommon but serious ones, such as diabetes mellitus, adrenal suppression, behaviour changes such as hyperactivity and aggression, weight gain and mammary hyperplasia or neoplasia (Stiles and Coster, 2016).)

Topical megestrol acetate

One study found that using a compounded topical 0.5 percent MgA suspension q8 to 12h was a successful treatment option for FEK in 15 of 17 cats (88 percent) (Stiles and Coster, 2016). No ocular irritation or appreciable systemic side effects were associated with its use. Cats with corneal ulcers went on to heal uneventfully while on treatment with topical MgA and an antibiotic. The decreased risk of systemic side effects and its relative safety of use in ulcerated corneas make topical MgA an appealing option, although its availability may be a limiting factor.

Allogeneic feline adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells

One study analysed the safety and therapeutic effects of subconjunctival implantation of allogeneic feline adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in five cats with EK refractory to conventional treatments (Villatoro et al., 2018). In all cases, a reduction of clinical signs was seen in the first four weeks, and complete remission with no systemic or local complications was observed after six months. This is interesting and promising, but the preparation of the adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells appeared time- and labour-intensive, and it is not currently available in the clinical setting.

Subconjunctival ciclosporin implants

As of yet, subconjunctival ciclosporin implants have not been reported in the management of FEK, but could be a consideration in patients not amenable to ongoing topical therapy (Padjasek et al., 2022).

So, how do we treat a case of feline eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis?

Overall, factors to consider when approaching a case of FEK and trying to come up with the most appropriate treatment plan include:

- Whether there is corneal ulceration and how worrying it is

- Any other concurrent ocular disease (eg non-healing corneal ulceration, additional conjunctivitis, keratoconjunctivitis sicca or symblepharon, which may be suggestive of FHV-1 involvement)

- Any concurrent systemic disease (eg pre-existing diabetes, obesity or heart disease may contraindicate systemic corticosteroid use)

- How easy it is for the owner to medicate the cat (ie whether the drop/medication regime is manageable). This is important since compliance is key to successfully treating this condition

- The cat’s temperament (eg would adding more medication such as an antiviral stress the cat even further, thereby triggering FHV-1 recrudescence?)

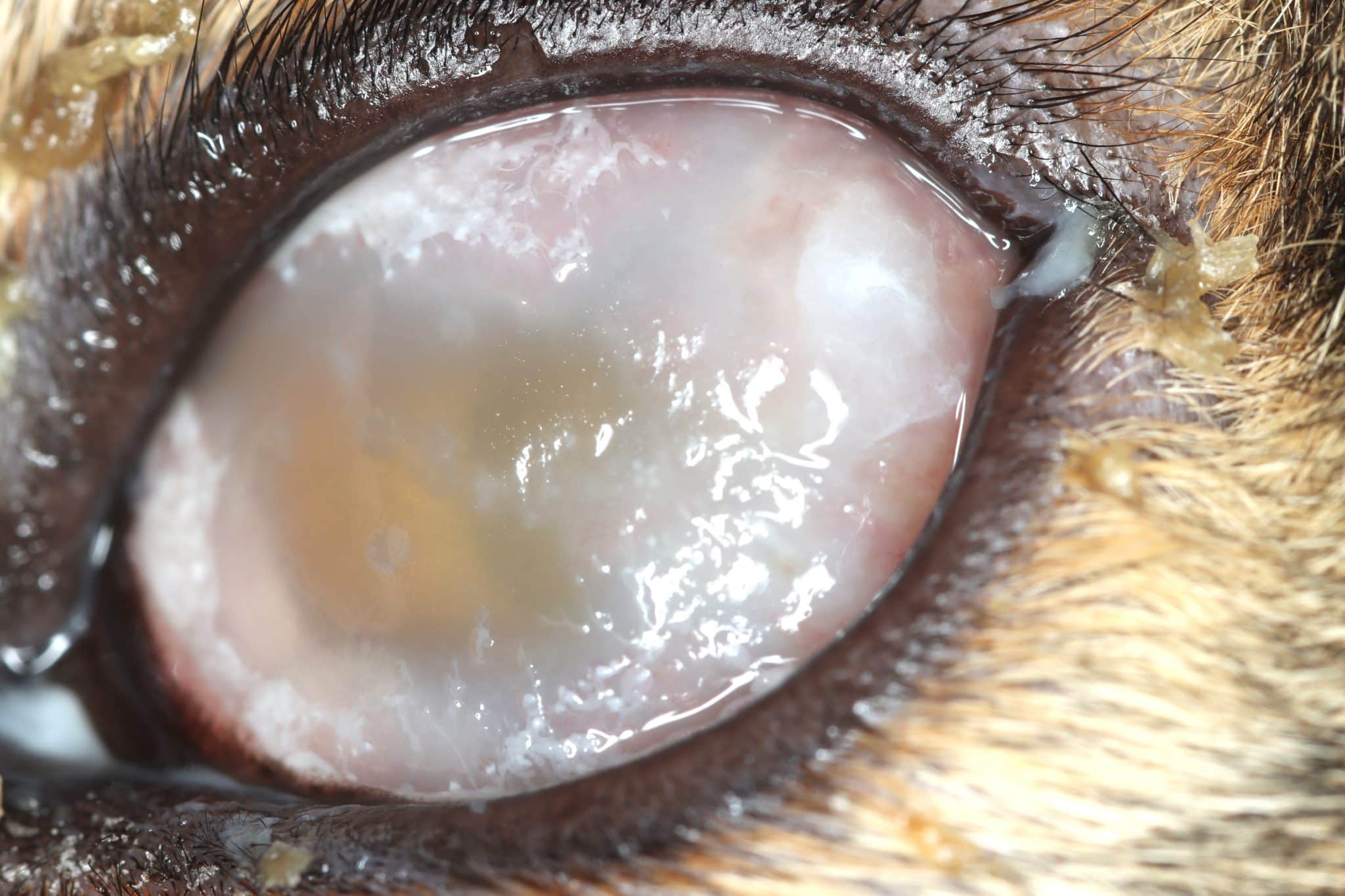

Prognosis

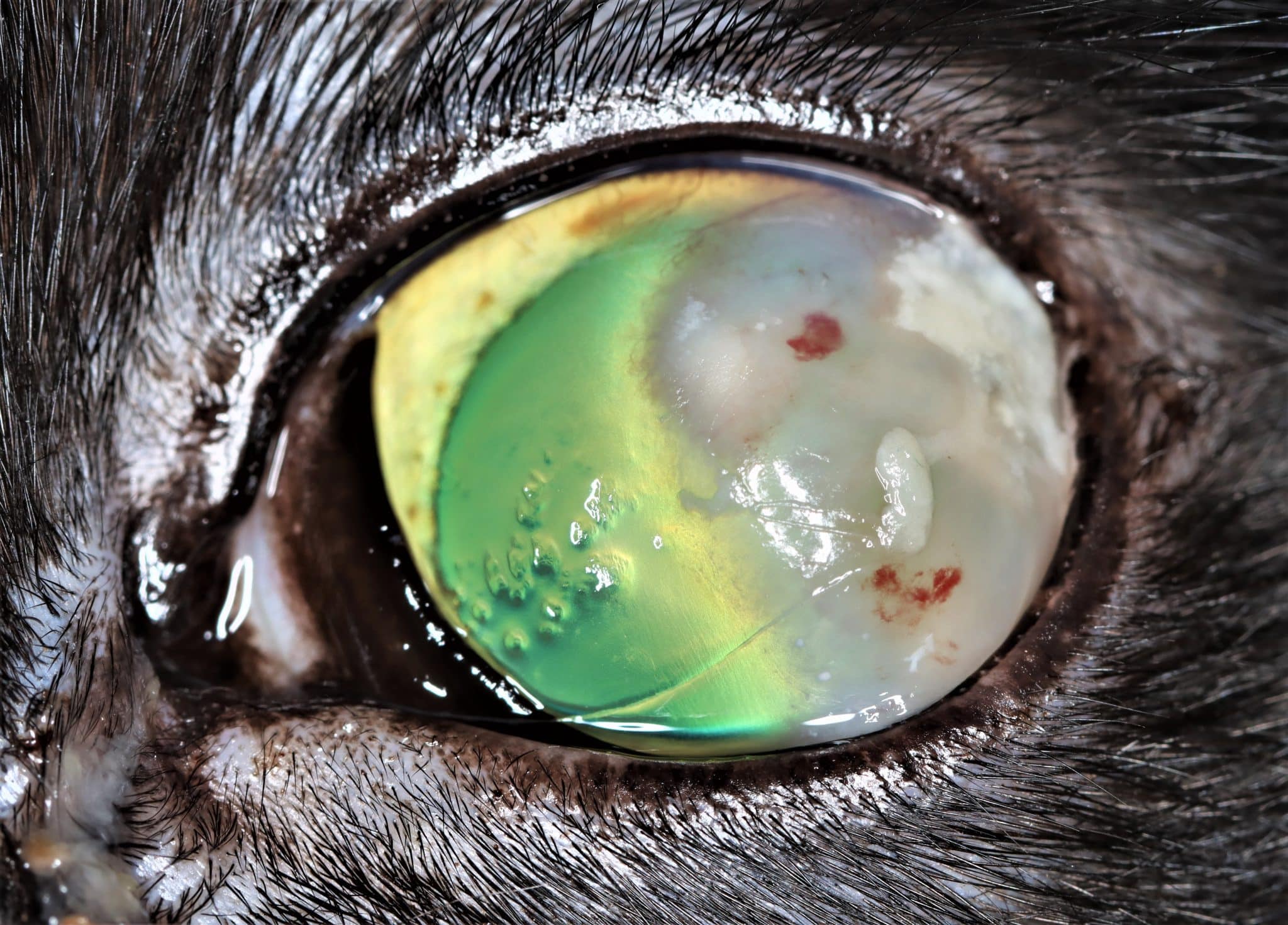

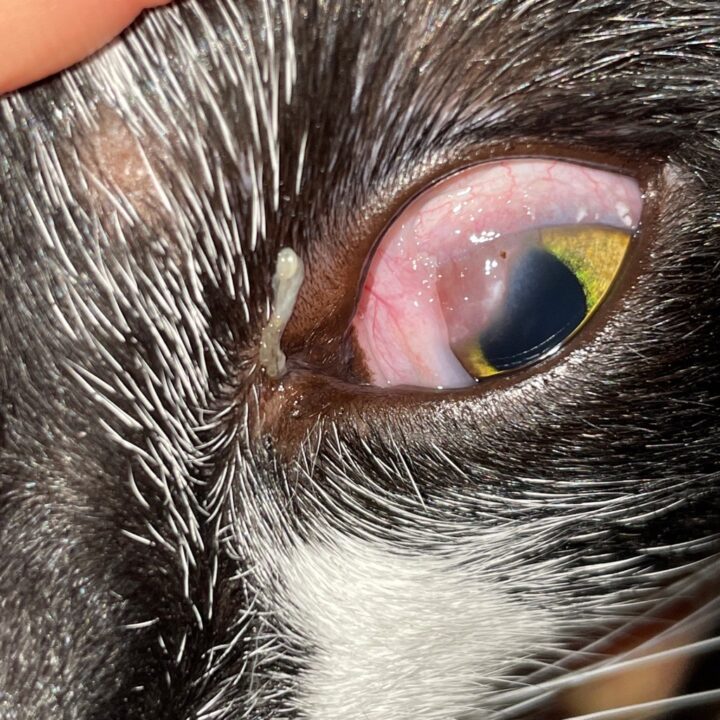

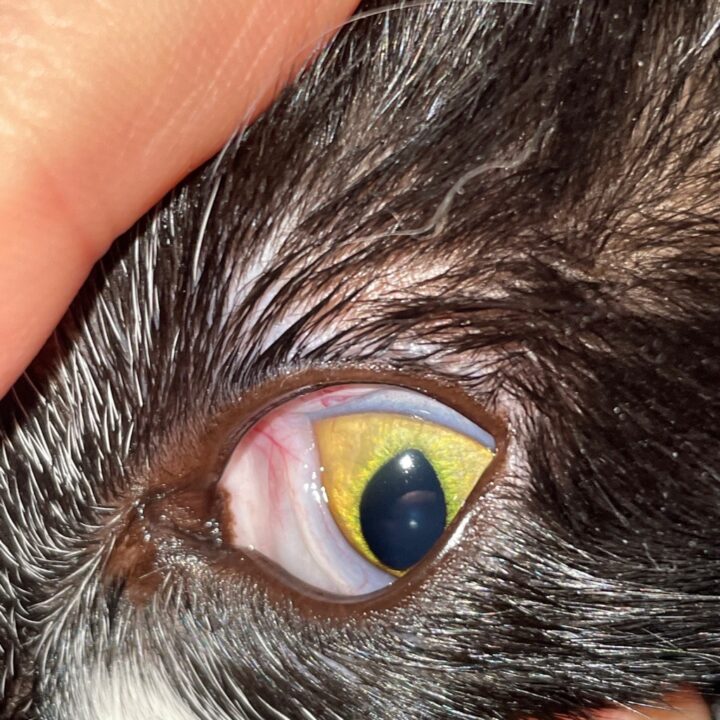

Most cats with FEK respond well to treatment and improvement can often be dramatic (Figures 6, 7 ,8, 9 and 10). In chronic, severe cases with a great extent of corneal pathology, some degree of corneal fibrosis is probably realistic, even once the active keratitis is controlled. Resolution of clinical signs is reported to be from two weeks to eight months, with a mean of around 2.5 months (Déan and Meunier, 2013; Morgan et al., 1996). However, recurrence rates for FEK are high, with one study finding 64 percent recurrence within 1 to 60 months (Morgan et al., 1996).

FEK is probably best described as a disease that cannot be cured, only controlled. This is helpful to bear in mind, particularly when counselling owners. Some cats can be slowly tapered off medication completely, but many require ongoing, lifelong treatment and flare-ups are always possible.

Food for thought

When systemic triamcinolone and topical tacrolimus were used concomitantly, Romaneck and Sebbag (2021) reported a rapid improvement of FEK by day 11, sustained clinical remission and no signs of recurrence at a one-year follow-up despite discontinuation of all medications by about the third month. Although these findings should be verified in future prospective controlled studies involving a larger population of cats, it may be that combined immunosuppressive therapy from the outset is preferred. Furthermore, as the authors suggest, being as “aggressive” as possible with immunomodulation chosen early on may make achieving clinical remission more likely.

In another relatively recent study that sought to correlate clinical and cytological findings in cats with eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis (Lucyshyn et al., 2021), slides and clinical images were scored using a standardised system. On cytology, considerable variation in cell types and their relative proportions were found to be present among FEK-affected cats. There were also interesting correlations between the cytological picture and various clinical features, such as the degree of conjunctival inflammation and discharge, corneal inflammation and fluorescein uptake:

- Eosinophil scores did not correlate significantly with total clinical corneal, conjunctival or fluorescein scores, suggesting that eosinophil abundance was unrelated to the degree of conjunctival or corneal pathology. In other words, only a few eosinophils may be noted despite substantial clinical disease

- Larger conjunctival discharge scores were correlated with higher cytological scores for eosinophils and neutrophils

- Higher neutrophil scores were associated with increased corneal opacity area scores

These findings led the authors to suggest that the cats in the study may have been manifesting different disease subtypes that are currently all categorised/considered under the umbrella diagnosis of FEK. If several subtypes of FEK do indeed exist, this may account for the differences in clinical course and treatment response among patients. It would be interesting if future studies enable the correlation of a patient’s specific cytological picture with medication choice and/or clinical prognosis.

Take-home messages

- To the untrained eye, FEK may be mistaken for a variety of conditions

- When in doubt, smear it out

- Treating FEK may well be a little more of an art than a science as it involves tailoring treatment to each individual patient. Various combinations of medication may be tried until the most effective regimen is determined

- Like any other immune-mediated condition, immunosuppressive corticosteroid therapy should be tapered very gradually no matter how rapidly clinical remission is achieved

- It is important to manage owner expectations by explaining the chronic nature of FEK and warning that it has a high chance of recurrence

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the ophthalmology team at North Downs Specialist Referrals, in particular: Dr Emily Jeanes for helping proofread and edit the article; Dr Adam Margetts, Dr Vim Kumaratunga, Dr Richard Everson, Dr Emily Jeanes and Dr Andra Enache, for the photographs; and all the above ophthalmologists for illuminating discussions on FEK.

Case Advice or Arranging a Referral

If you are a veterinary professional and would like to discuss a case with one of our team, or require pre-referral advice about a patient, please call 01883 741449. Alternatively, to refer a case, please use the online referral form

About The Discipline

Ophthalmology

Need case advice or have any questions?

If you have any questions or would like advice on a case please call our dedicated vet line on 01883 741449 and ask to speak to one of our Ophthalmology team.

Advice is freely available, even if the case cannot be referred.

Ophthalmology Team

Our Ophthalmology Team offer a caring, multi-disciplinary approach to all medical and surgical conditions.